Even at £634,000, McLaren didn’t charge enough for the F1. Revisit our feature from January 1997, where Michael Harvey looks at why the car didn’t do the business – and meets Derek Waelend, the ex-Ford cost-cutter who save McLaren Cars’ bacon.

A little under a year from now, the McLaren F1 will be history. The plum and grey composite shells currently bringing up the rear of the production line in Woking carry chassis numbers 77 and 75. Eight of the ugly new, long-tailed GT race cars follow, at least one of which must be a road car. Then come a further 15 regular F1s. And then… Then nothing.

From Ron Dennis down, McLaren folk talk about ‘the next project’, but it’s not client confidentiality that’s stopping them from saying more. There just isn’t any more to be said. Right now, officially, there is no second project.

This isn’t how it was supposed to be. When McLaren cars was founded back in March 1989 (technically it had already been around for three years as TAG McLaren R&D), Ron Dennis, TAG McLaren chairman, said he wanted it to be more than just a one-project wonder. ‘I’d like to think,’ he said at the time, ‘we’re starting a new British car company…’

Dennis recognised that, with five world titles behind it, the McLaren name was ready to earn money outside grand prix racing. An electronics company, a marketing services operation and a road car would all enhance the McLaren name and reduce its dependency on motorsport and cigarette money.

But the F1 was created primarily to make money for Dennis and his partners, the enigmatic Oijeh brothers of Riyadh. Back then, before Black Monday, there seemed no end to demand for 200mph, £200,000 supercars; Dennis, stuck in the small world of F1, wasn’t to know what was around the corner. He had every reason to believe his design team, led by Gordon Murray, would trump everyone’s aces, Ferrari’s included. If people were prepared to pay $17m (£11m) for a 27-year-old Ferrari, why shouldn’t they pay US$1m (£634,000) for a new McLaren?

The game plan was based on a short lead time — less than four years to the first customer car — and, following grand prix practices, a surprisingly small development budget and small investment in tooling. The F1’s price, US$1m, and limited production run of 350, were announced three years later on the eve of the 1992 Monaco Grand Prix. But by then the market had already changed. Dennis announced the F1’s premature demise, 250 cars and three years early, late last year. He made no bones about it; The F1 has achieved all its objectives. Except maybe its financial ones.’

It’s a popular myth that the F1 project has been a black hole for McLaren, incurring losses of millions of pounds. Not so. When Ron Dennis waves goodbye to the 100th F1 next year, it’ll be with a warm glow in his current account. And that’s thanks, in no small part, to a million-words-a-minute Midlandser, Derek Waelend.

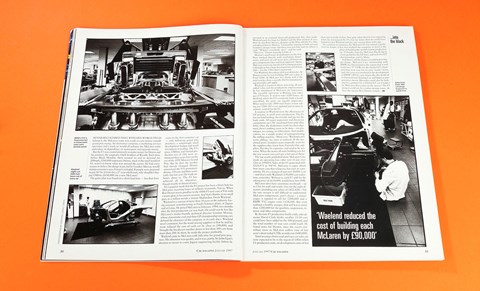

Waelend is a veteran of more than 30 years in the industry, having overseen manufacturing at Ford’s Valencia plant, at Jaguar and at Lotus. He joined McLaren in February 1994, two months after the first production car was built. He could not be less like McLaren’s media-friendly technical director Gordon Murray, whose charismatic cool and three GP championship-winning cars defined the character of the company in its early days. Waelend won’t comment, but the word among suppliers is that he and his team reduced the cost of each car by close to £90,000, and brought the breakeven number down to less than 100 cars from more than 200. In short, he made the project profitable.

Waelend came to McLaren with little time for grand prix practices. His obsession was quality, and it was, partly, Sir John Egan’s decision to invest in a new Jaguar engineering facility before he invested in an essential doors-off production line, that made Waelend pack his bags for Hethel and the Elan project.

It was there he met Peter Stevens, designer of the Elan and the F1, who introduced him to Murray. ‘I remember coming to look around Gordon’s design room and there was just him and six others. I said, “Where’s everybody else?” and he said, “This is it.” I knew instantly I’d like it.’

Murray’s small team of draftsmen on the first floor worked directly with machinists down-stairs, and were on call seven days, 24 hours to give components once and final approval. Again, McLaren won’t say, but this GP working practice is thought to have kept development costs below £6m – not the £30m that’s rumoured.

For Waelend, the culture shift was dramatic. At Browns Lane he was building 200 cars a day, at Ford 1200. At McLaren he’s doing well if the total reaches three a month. But his manufacturing principles still apply.

Waelend is fanatical about removing all non-added value and the productivity improvements he has introduced at McLaren are impressive. The assembly operation at Woking now takes just 670 hours. It used to take 1200 hours. At Shalford, where the F1’s composite body is hand-assembled, the gains are equally impressive. What used to take 3000 man-hours is now taking just 1200. He’s even updated just-in-time inventory control for the F1.

A surprise to Waelend were the efficiencies of GP practice in small series production. The F1 has no hard tooling, the moulds and jigs for the body aside. All major suspension and drivetrain components are CNC-machined from solid alloy billet. Once the draftsman’s work has been digitised, there’s nothing more to be done – no prototypes, no casting, no fabrication. And modifications are a simple matter of reprogramming the milling machine.

‘Mind you,’ Waelend can’t resist adding, ‘we soon resourced all the machined parts. Gordon’s team originally went for the suppliers they knew best, Formula One suppliers. But they’re expensive and tend to be seasonal. When the teams all start building cars for the new season you can’t get a fart out of them.’

The last results published show McLaren Cars made an operating loss (after tax) of just over £2m in 1994/95. Sales of the F1 generated only £124,971 in ’94/’95. McLaren is cagey about how many cars that relates to, but even at a pessimistic 20, its a margin of just over £6000 a car – and that’s with Waelend’s £90,000 cost reduction, remember. Without it, each F1 sold for the asking price of £634,000, would have lost £84k.

McLaren does have enormous overheads – up to £3m for staff and nearly £lm for the eight directors (including one salary of £422,828) – but the tiny margin is still difficult to understand. McLaren components aren’t cheap – a monocoque is reputed to sell for £200,000 and a V12 engine costs £128,000. But even without a healthy margin, that still leaves more than £200,000 for the gearbox, suspension, interior and other components.

By the time F1 production finally ends, sales director David Clark thinks another 15-20 cars could have been added to the 100 planned, and the total number of race cars could reach 30. Good news for Dennis, since the racers contribute more to McLaren coffers (one of last year’s short-tailed GTRs would cost £680,000).

Total revenues from road and race car sales are now expected to be in the region of £40m when F1 production ends, on development costs of less than one-seventh of that. Not quite what Dennis was expecting when he announced the F1, but far better than he could have hoped for pre-Waelend and pre-race success three years ago. So, contrary to rumours, the McLaren F1 has turned a profit. Lest we forget, it has also enabled the company to revel in the glory of building the world’s fastest production car (231mph), kept the McLaren Flag flying in a lean period for the GP boys, and won two GT championships and Le Mans.

And there’s still the chance it could lead to bigger things. McLaren Cars’ relationship with BMW has blossomed to the extent that it will build two ’97 GTRs for the Global GT championship next year for its own ‘works’ team, and, this year, was involved in the development of BMW’s BTCC cars. Ironically, the death of its International Touring Car and Indycar programmes means Mercedes could also be looking for a partner for a Global GT car.

Could it be McLaren that comes to the rescue? The F1 project could yet, by a rather strange route, deliver the success Ron Dennis craved…

First published in January 1997

Read more: A McLaren milestone: 10,000th car built in Woking