► Crossing the Channel…

► …in a floating kit car

► What could possibly go wrong?

They said it couldn’t be done. Colin Goodwin strikes out for France in Dutton’s floating Fiesta.

Never thrown up in a car before. Mind you, I’ve never tried driving to France in one, either. And I don’t mean driving onto a ferry or le Shuttle, but actually driving to France, on a wet bit called the Channel. I’ve wanted to do this ever since I heard the grim news that we would not be driving our cars through the Channel tunnel, but putting them on trains instead. What a swizzle. I had visions of blatting through the tunnel in a wailing Ferrari and then popping out on the other side like a bullet. I’ll show them, I thought: I’ll find a car that can drive across the drink.

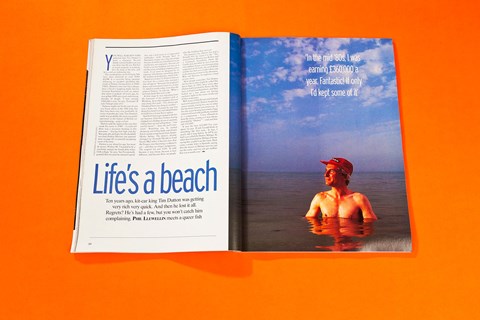

Now, if you scan through CAR’s GBU section you will see that although there are many vehicles with impressive performance figures, none of their claims is in knots. But then we received a press release from a French company whose ‘Hobbycar’ could allegedly swim, as well as drive. So we rang them up to see if we could borrow one to cross the Channel. Non. I can’t remember their exact words, but it was something like: ‘you must be crazy. Besides, our car is designed only for rivers and lakes.’ Blast – scuppered already. Until, that is, I heard about the Dutton Mariner, the work of well-known kit-car builder Tim Dutton. A few derogatory words about the French and some fiery talk of the British spirit of adventure had Dutton hooked.

And that is how I happen to be bobbing about in the English channel, feeling more than somewhat Uncle Dick.

Now, so that you fully appreciate the lunacy of what follows, I think we should welcome you aboard our vessel and acquaint you with its workings. We’ll do this on dry land, because clambering about on the Mariner when it’s at sea is likely to resort in a swim.

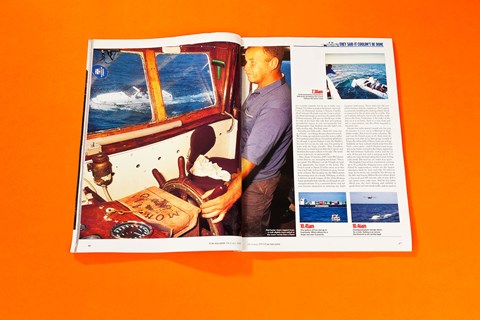

As you can see, the Mariner is not going to have Giugiaro crying onto his drawing board with envy. But then to be fair to Tim Dutton, designing a vehicle that is half boat and half car is no easy brief. You are, for one thing, committed to making the bottom half hull-shaped. Ironically, it’s when the thing’s in the water that it looks at its best as a car – and when it’s out that you realise it’s a fairly smart boat.

The Mariner’s hull/body is, sensibly, made from glassfibre, unlike the 1960s Amphicar (the most famous of all amphibious cars) whose steel body didn’t stand up well to saline dips. Dutton is the master of building interesting cars cheaply, so he uses a Ford Fiesta powertrain and running gear for the Mariner. In this car, the second one built, XR2i bits are used.

The engine and transmission go straight in, but the driveshafts are fitted with stainless steel bearings where they pass through the hull. The driveshafts and steering rack ends are topped off with well sealed rubber boots, but if any water does enter the engine bay it’s pumped out by a bilge pump. At the back of the Mariner is a Fiesta beam and axle struts. And now the bit you’ve been wondering about: how is it propelled? The Mariner has a water jet drive, like a jet ski. The jet unit is driver by a hydraulic motor, which is powered in turn by a hydraulic pump fitted to the engine. To engage the jet drive all you have to do is stick the Fiesta gearbox into neutral and pull a lever that starts the hydraulic fluid pumping. Next to this lever (between the front seats) is a red-knobbed lever that selects reverse – a simple hood that redirects the jet’s woosh under the hull. Steering, we’ll come to in a minute.

So at 6.30am, Folkestone Harbour, we drive down the slipway, pop the car into neutral, pull the aforementioned lever and – presto! – it’s a boat. Now, there aren’t many things I wouldn’t do to provide you lot with entertainment, but I’m afraid that drowning is one of them, so we have chartered Jeff Jekabson and his 50ft fishing boat, Lynx, to escort us to France (we’ll land somewhere near Boulogne). I take comfort in the fact that Dutton is a poor swimmer: his presence today indicates a certain faith in his creation. I swim quite well for a fat slob, but only in warm waters.

The harbour is tranquil and very picture-postcard in the golden sunrise. I suppose by seafaring standards the sea is pretty smooth, but to me it looks very choppy. I’m rather scared, to be honest, and wish I was on Dartmoor testing a Toyota Corolla diesel instead. Oh God, even the Lynx is pitching about alarmingly as we leave the safety of the harbour entrance. Jeff says we should stay on the left side of his boat (the side that isn’t getting pounded by waves, to you non-nauticals) but photographer Tim Andrews says the light’s not right on that side. Too bad, mate.

Actually, our little craft – about the same size as a Fiesta – isn’t being thrown about too much. We’re rising up and down over the waves, rather than getting tossed about. I’m getting splashed a lot, though. Captain Dutton is not, the blighter, because he’s on my lee side (see, I’m getting to grips with the lingo already). Also, Goodwin (first mate) is much heavier than the captain and therefore the water collects in his side. The windscreen wipers are on permanently.

After about 10 minutes, Jeff’s mate Phil shouts that we are averaging two knots. This is not good. The Mariner can do 95mph on land and, apparently, 5 knots in the water. The French coast is 25 miles away so at this rate it will take at least 12 hours to cross. I want to be at home. But we press on, the XR2i motor thrumming away at a steady 3000rpm, at which it delivers its peak torque, all the while blowing basso profundo farts into the sea through its sub-merged exhaust. It is a constant drone and our ears become attuned to it, noticing any slight variation with panic. Those who run old cars will be familiar with the experience. The Captain is constantly twiddling the steering wheel which is connected to the jet drive unit by a cable. The car’s wheels still turn, but it’s the jet that really moves the boat. Understeer is the order of the day (as it is in land). Turn-in is very slow and feel is non-existent, but the effort required is minimal, too.

Twenty-five miles doesn’t sound very far: just 20 minutes in a car (or in a Mariner in land-lubber mode) But at sea it’s quite a distance. We can’t see the French coast at all, And, more depressing, even after we’ve been going a couple of hours, the white cliffs of Dover look just as huge. Suddenly, we hear a chunk-chunk noise from the back – sorry, stern – and it’s Dutton’s turn to get wet as he furtles around in the bilges, tightening the belt between hydraulic motor and jet unit. It has got wet and is jumping teeth. It is when we stop driving/sailing that I start to feel a bit crook. But soon we are under way again.

The English Channel has a motorway running up it. It’s called the shipping lanes, and is traficked by supertankers, which are the largest structures built by man and take 10 miles to stop. To be hit by one would be like driving up the M1 and having Milton Keynes whizz down a slip road and biff into the side of you. Jeff is our green cross code man. And he has radar. Mind you, the sun’s shining and visibility is good, there isn’t too much traffic and we seem to be going along very nicely, thank you. Our speed has increased to over three knots (thanks to the tides and following wind). Spirits on board are high. Captain Dutton has to tighten the belt again, but all seems well. Life on the ocean waves, blah blah.

There are no Little Chefs in the Channel, so food is passed to us in a fishing net from the Lynx. It sounds easy, but passing things from one quite large bobbing vessel to a very small bobbing vessel is actually rather tricky. There are also no petrol stations, so a barrel of four-star has to be passed over to us. I cannot believe that Dutton has fitted a locking petrol cap to the Mariner. This means he has to take out the ignition key and hang over the side to unlock the cap. If he drops the key we’re stuffed and I will mutiny and set him adrift, like Captain Bligh. Pouring five gallons of juice through a funnel when you’re being pitched about is about as easy as threading a needle after drinking a bottle of Captain Morgan rum. A fair bit is lost – in the Channel and up my sleeve.

While we’re filling up, we are strafed by a low-flying coastguard plane: we are in the shipping lanes so must get under way as soon as possible. The plane makes a lot of swooping passes, but we resist the temptation to wave. Though British-registered, the coastguard plane is shared with the French. The Brits are not too keen on trips like ours, and tried to put us off. The French are dead against them, and have some law that says you can’t go more than 300 metres from shore in a boat (or car) as small as ours. But I have terrible trouble understanding some laws – speeding ones, for example – and shall ask the French to kindly clarify this legal point once we’ve landed.

When we’ve landed. Yes, I really do think we’re going to make it. We can now see the French coast quite clearly, and the white cliffs of Dover not so well. Soon we are joined by a French trawler, out of Boulogne, that circles us. At first the crew just look on bemused; then they return our waves. Captain Dutton and I are ecsatic. It’s great to be British and eccentric and doing something crazy. I can’t wait to see the look on the faces of the French holidaymakers when we arrive on the beach. It’s half past midday, we’ve been at sea for six hours and we’re probably only two hours from France – perhaps less, because we’re picking up a favourable tide.

And then disaster strikes. For the whole trip, puffs of steam have been escaping from the engine bay vent as water hits the hot exhaust silencer. But suddenly we realise that the steam looks thicker than usual and is in fact smoke. And then I see flames. Christ, we’re on fire! An inadequate-looking fire extinguisher puts the flames out, and Dutton climbs around the front of the Mariner to inspect the damage.. The wiring loom has been toasted. He can fix it, but we’re still in a sea lane and Jeff says it’s too dangerous and too illegal to hang around in it while Dutton cuts out the burnt section of loom and splices the wires back together. He has a quick go but it’s going to be a long job. I throw up over the side. But I’m more than physically sick. We are so near now – Jeff reckons only five miles off the coast and probably less than an hour away at our improved speed.

All the joking has stopped. The Lynx will have to tow us back to Folkestone and we will have the misery of seeing all the tourists and daytrippers laughing at us as we limp in.

As we sit on the Lynx, chugging the three to four hours back to England, Tim Dutton sits on the deck with his head in his hands. I have never seen a man so dejected. We were so near to our goal, stymied by such a simple thing (it turns out that the fan that cools the engine bay had failed, allowing the exhaust to get hot enough to set fire to the marine ply bulkhead).

We are all gutted, but I try to cheer Dutton up. The Mariner is intended to be a bit of fun (cheap fun, too, for £4000 will buy you the kit – all you need then is a Fiesta donor car) for use on rivers and lakes. That it failed by five miles to cross the Channel is no disgrace. It got 20 miles, after all.

When we arrive back at Folkestone, a TV crew is there to meet us. ‘Are you going to try again?’ they ask. ‘Damned right’ says Dutton. And so, next June, if you happen to be on a Channel ferry, look west, for you might see Captain Dutton and his first mate, Goodwin, driving to Le Mans. Non-stop.