► Sebastian Vettel leaves Ferrari after five years

► But why did it happen?

► Could it be the Ferrari mentality?

After five years and 14 wins, the Vettel and Ferrari experiment has ended. In a statement released today, the four-time world champion said ‘in order to get the best possible results in this sport, it’s vital for all parties to work in perfect harmony.’

‘The team and I have realised that there is no longer a common desire to stay together beyond the end of this season.’

According to the German and the team, it’s not about money and paddock intel suggests it’s not about retirement either; Vettel is rumoured as talking to at least one other team about his future in F1.

Team principal Mattia Binotto confirmed: ‘There was no specific reason that led to this decision, apart from the common and amicable belief that the time had come to go our separate ways in order to reach our respective objectives.’

So what went wrong?

Not money, not performance – so what’s left? Of course, Vettel’s departure could be down to the sheer pace of his new teamate Charles Leclerc, who won more races than he did last year. Vettel didn’t dominate the Monegasque in the way we expected in 2019, and that could have forced his ‘fight or flight’ reaction, much like it did with Daniel Riccardo at Red Bull.

However, it’s worth looking at the mechanics of the Ferrari team itself. Prost, Alonso and now Vettel were all proven champions who moved to Maranello with big plans – only to leave disappointed. In recent history, Schumacher is the exception rather than the rule.

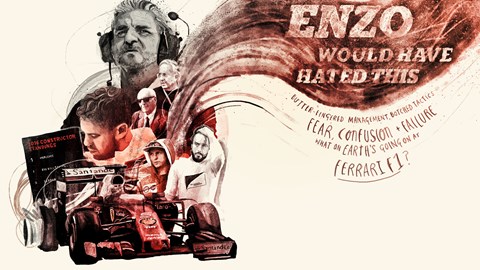

So is it something about Ferrari’s passion and politics that just makes it impossible to win – even when it builds the fastest car? We’ve dug up a feature from our December 2016 issue that explores that theory. The team principal is different, and it deals with Alonso rather than Vettel’s departure, but they’re interchangable. In the midst of intra-team conflict, the 2016 season had themes which we’ve seen ever since, and themes that have surely helped Mercedes to a record six titles in a row.

The names that come up are also telling: Aldo Costa joins Mercedes after being let go by Ferrari, and so does Ferrari’s technical director James Allison. The latter is now the third face of the Brackley-based trio, alongside Toto Wolff and Lewis Hamilton.

December 2016 archive story: what’s going on at Ferrari ?

In the end, Fernando Alonso was right. He left Ferrari at the end of 2014 because he couldn’t conceive of a way that the team was going to win the world championship during the remaining two years of his contract. How prophetic his decision turned out to be.

There were moments in 2015 when the Scuderia looked to be making progress, notably Sebastian Vettel’s three race wins, but in the end the team did what Alonso knew it would: it flattered only to deceive. When the Scuderia was required to step up in 2016, it failed to deliver. And now many Italian commentators close to the team are starting to demand answers. Enzo Ferrari himself, they believe, would be appalled at the way the team is being run.

Is it the car?

There was nothing fundamentally wrong with the SF16-H; it wasn’t the equal of Mercedes’ W06, but it was well balanced and good enough to win races. However, it failed to achieve its potential after some lacklustre performances that left even the most ardent Ferrari apologists feeling bewildered. Had Alonso still been at the team, he would most likely have retired or said something inappropriate and been sacked, as happened to Alain Prost back in 1991.

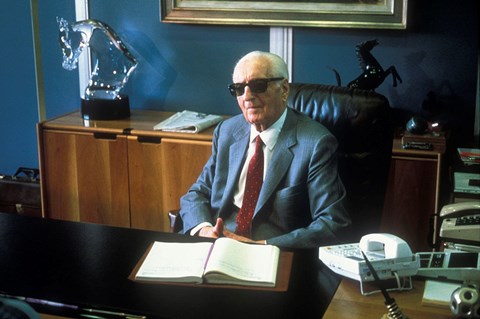

‘Ferrari are attracting a lot of negative headlines at home,’ says the doyen of Italian F1 journalists Pino Allievi, who was close to Enzo (below). ‘This will continue until the victories come again, but it’s hard to know when that will be because their problems appear to be deep-rooted.’The problems are deep-rooted because there’s no single source. There wasn’t a clear lack of downforce or horsepower on the SF16-H at which to throw time and money; the chassis wasn’t bad; the engine was the second best after Mercedes; the drivers did a solid job and the team continued to hold more political clout in 2016 than any other team.

Ferrari were a little bit off in every area this year and there was no straightforward solution. Push- or pull-rod suspension? The position of the turbo? Long or short nose? These were questions that needed answering, which is why the team persevered longer than expected with the current car; they wanted to understand where it was lacking, which took away resource from the 2017 car. That could cost them going forward. But the problems were not only technical in 2016; they were managerial as well.

Is it the management?

Had the team not created its own headlines, who’s to say the rest of the programme wouldn’t have slotted into place? Without the pressure created by some ill-advised quotes from senior management, who’s to say the team wouldn’t have maintained the momentum gained in 2015? There has been a lot of change at Ferrari in recent years.

A new management team was put in place at the beginning of last year, replacing the short-lived tenure of Marco Mattiacci. In came Maurizio Arrivabene, formerly of Philip Morris, as team principal and new Ferrari president Sergio Marchionne. Two slightly gruff, old-school Italians, who liked to issue threats as a means of motivation. Both men got it wrong during the course of the year, with Arrivabene still making mistakes at the Japanese Grand Prix, where he told the Italian media Vettel would need to earn his place in the team beyond 2017.

The same Vettel who made Arrivabene look good last year by winning his second race in charge. ‘I don’t know why he [Arrivabene] would say something like that,’ said Red Bull boss Christian Horner. ‘Sebastian is just about the biggest asset he’s got.’

In many ways, Ferrari have been a victim of the few successes they achieved last year. After that win in Malaysia 2015, Arrivabene couldn’t hide his delight. He joshed with the media, saying he’d get a new tattoo to mark the landmark occasion, and he said he expected more wins. When the team took further victories in Hungary and Singapore, there was genuine reason to believe that Ferrari could consistently challenge Mercedes in 2016. ‘If we make the gains over the winter that we expect to make,’ said technical director James Allison, ‘then we hope to take the fight to Mercedes next season. For the good of the sport, I hope we can do that.’

James Allison

Allison’s air of optimism, built on 18 months of solid progress, was felt throughout the team. Ferrari looked a more cohesive unit than it had done in years and you sensed there was a desire to prove Alonso wrong.

The impertinence of it! No driver is bigger than Ferrari. But those calm winds of optimism were to be short-lived. Within weeks, the feelgood factor had been replaced by uncertainty. ‘If I can give some advice to all those who work in Maranello,’ said Ferrari president Sergio Marchionne before Christmas, ‘it is to be terrified of the arrival of Spring.’

They were harsh words and Marchionne couldn’t claim to have been misquoted or lost in translation because he uttered them on television and he speaks English fluently. His threat was pointed and clear. Anything other than a title challenge in ’16 would be unacceptable, and he was pointing his finger at Allison.

That seemed unfair, given the turnaround experienced by the team under the Englishman’s technical stewardship. Allison is respected and liked. In this post-Adrian Newey F1 landscape, he’s regarded as the best aerodynamicist in the business and a man with a natural air of authority. When he addressed the Ferrari factory after the opening of its new wind tunnel in January 2014, he announced that the team could finally fight without one hand tied behind its back. He was given a raucous standing ovation. Yet Allison was now the man under pressure.

The lure of success in 2016 had been replaced by a fear of failure, stifling creativity in the design office and on the pitwall, where some question-able strategic calls were made. When we heard Vettel deciding his own strategy during the German Grand Prix, we started to understand the term ‘corporate constipation’.

Corporate constipation

People at Ferrari seemed afraid to make decisions, in case they were the wrong ones. Everyone was affected by this apathetic attitude; even Vettel’s pace dropped off. The gap between him and Kimi Räikkönen reduced dramatically in 2016, with Kimi’s impervious character proving more adept at dealing with the uncertainties flowing through the team.

Yet, even with the ludicrous headlines being created by the management, 2016 could still have turned out differently. Had Vettel won the season-opener in Melbourne, which he was leading until it was red-flagged and Ferrari inexplicably chose not to change his tyres, the momentum gained might have created a more positive atmosphere in the team. As it was, the team went to the second race in Bahrain on the back foot and left the Middle East in even more introspective mood after Vettel’s engine failed on the formation lap.

After two races Vettel was 50 points behind Nico Rosberg in the championship standings. Marchionne ramped up the pressure by turning up at the third race in China to find out what was wrong and, in hindsight, that was the moment when the season was lost. Performances went from bad to worse.

Adding to Ferrari’s problems was the personal tragedy that had befallen James Allison. His wife, the mother of his three children, had died suddenly after the Australian Grand Prix and James had returned to England on compassionate leave. The team was quick to say that its development plan wouldn’t be affected, but Ferrari was overlooking the fact that Allison had reorganised the technical department last winter to allow him to take more of a hands-on role back at base.

He’d drafted in Jock Clear from Mercedes to oversee trackside engineering, leaving him with more time to focus on development. While Allison was in England, Ferrari’s on-track performances suffered.

It was clear by the British Grand Prix that any chance of a championship challenge was gone. Allison, being the ever-practical engineer, suggested to Marchionne that the team should turn its design focus to the 2017 rule changes, effectively writing off the second half of 2016. Marchionne was having none of it; the email announcing Allison’s departure from the team came through a few days later.

Errors

True to Marchionne’s word, Ferrari continued to develop the car. At Suzuka in October the SF16-H turned up with a new front wing and new bargeboards and its one-lap pace improved immediately. Vettel and Räikkönen locked out the second row of the grid, ahead of both Red Bulls, their rivals for second place in the constructors’ battle. But who really cares whether Ferrari finishes second or third in the championship?

Alonso didn’t, which is why he left two years earlier and it’s disappointing to think that Ferrari isn’t solely focused on winning. By prolonging the agony with the current car, the team has harmed its chances next year by delaying the aerodynamic programme. Another questionable management decision. So what happens next in Maranello? How does the team get back on terms with Mercedes and Red Bull, both in the short and long term?

If the management has learnt anything in 2016, it has to be this: don’t instil a culture of negativity by making outrageous comments to the media. Ferrari’s last era of dominance was overseen by Jean Todt, who was a brilliant politician. He worked tirelessly to protect the race team from the politics created by senior management; it would have been anathema to him to be the source of the negativity about his own team.

Marchionne and Arrivabene, take heed. On an operational level, Arrivabene needs to improve his English, the common language of the F1 paddock. He has no rapport with the media, except for a handful of Italian journalists, because he worries about being misunderstood.

Even the FIA prefers not to use him in its official press conferences for this reason. His replacement? Jock Clear, who’s time would be better spent focusing on the engineering of the cars. Looking further ahead than next year’s car, the concept for which has already been decided, Ferrari is intent on promoting Italian engineers within Gestione Sportiva.

‘We can be successful using Italian engineers,’ says Arrivabene. It’s a romantic idea and it’s in keeping with the philosophy of the GT division, but F1 is too hard-nosed for romanticism. Moreover, the horse has already bolted because Ferrari had the best racing car designer in the world on its book, an Italian called Aldo Costa, but they let him go in 2011. To Mercedes.

A logical extension of how best to ensure Ferrari has the best talent in its F1 team would be to be set up a design office in the UK, similar to the Guildford Technical Office set up by John Barnard in 1988.

Enzo Ferrari detested the notion of F1 being a British sport, but that is the reality. Eight of the 11 teams are based in the UK; it’s where the expertise is located, and Ferrari needs to have a presence in the UK to tap into that talent pool.

As you might expect, there is some scepticism in Maranello. ‘You know what remains my biggest regret for the years in which I was in charge of the team?’ says Piero Ferrari, the only living son of Enzo. ‘It was to convince my father that there was still the need to rely on a great designer from the outside. But Barnard never interacted with our culture; it was a big mistake.

Are Mercedes any less German for having a racing team based in the UK? Are Renault less French for the same reason? Of course, they aren’t. Had something akin to the GTO existed – or even been in the offing – five years ago Adrian Newey would have moved to Ferrari. Alonso was promised a Newey-designed car when he signed for the team, but logistics prevented the deal from going through. But a GTO-type set-up is all in the future, or maybe never, if Piero Ferrari continues to wield influence in the corridors of Maranello.

The immediate future looks tricky for Ferrari; because the sport is about to go through its biggest aerodynamic rule change for 10 years and Ferrari has just parted company with the best aerodynamicist in the business in James Allison. When, as many people predict, the team makes a slow start to 2017, Marchionne will have to resist the urge to issue threats.

He’s seen the damage his comments did last year; if he were to do it again, the Scuderia itself could be under threat. After all, it’s now a publicly quoted company, and faces the possibility that its long-standing $100m payment advantage from Bernie’s F1 could be slashed by the sport’s new owners. Shareholders may rebel if the numbers cease to add up. F1 without Ferrari seems unthinkable, but Marchionne is a businessman, not a sentimentalist. In 2014 he said: ‘If we don’t improve quickly we will have to consider our long-term future in F1 because this level of performance is affecting our credibility in the road car market.’ For Ferrari as a business and for F1 itself, the stakes are perilously high.