► Tough CO2 limits coming to Europe

► Fleet average must hit 95g/km by 2021

► Why the UK is trailing this target

The new car sales figures for 2019 contain a harsh detail: the UK’s new-car fleet average CO2 emissions rose for the third year in a row, as buyers plumped for thirstier SUVs and swerved diesels.

Today’s cars are considerably cleaner than previous decades and the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) claims the average new car sold last year emitted 29.2% less CO2 than those released in 2000.

But there’s no getting away from the fact the UK new-car fleet average CO2 rose for a third consecutive year in 2019 – up 2.7% to 127.9g/km. It makes the industry’s goal of averaging 95g/km by next year a seemingly impossible mission. Read on for our explainer and to find out why popular models such as the Mazda MX-5 are likely to disappear from price lists in the months ahead.

Why manufacturers must average 95g/km of CO2 by next year

Think electrification is something for other drivers? Think again. Within two years, car makers may have to ration petrol car sales to hit CO2 targets, or face multi-million-euro fines. This is why Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) and Tesla are working up a carbon swapping scheme, with Fiat paying the electric car maker millions of euros to dodge fines in Europe for missing carbon targets.

Groups that have been slow to embrace plug-in cars – Ford, Fiat-Chrysler, Mazda, PSA Groupe – will almost certainly have to cap their own sales until their product range catches up with the regulations. The industry is furiously developing pure EVs, and plug-in and mild hybrids: it needs them on the market as soon as possible, ahead of new emissions targets coming into force in 2021.

The Financial Times claims that FCA and Tesla have formed ‘an open pool’ of vehicles, basketing their combined sales for the purposes of European regulation. It based its story on declarations made with Brussels, ahead of the 2021 targets which specify group CO2 emissions must not surpass 95g/km.

This countdown is focusing minds big-time. European Union legislators have introduced the world’s toughest emissions regulation: new cars sold in the region must emit on average 95g/km of CO2 by 2021. At the end of 2017, the industry’s cars were averaging 118.5g/km and that figure is rising in many countries, including the UK. There is no doubt that some car makers will miss their individual targets, typically calculated on a group-wide basis and making allowances for vehicle weights. Any group that misses its target will be hit with swingeing financial penalties.

The best electric cars: our guide

CO2 emissions targets for 2021: car makers face millions in fines

‘The fine for 1g over your target is €95 multiplied by all of your volume,’ says Kia Europe’s Artur Martins. ‘For Kia that’s 500,000 cars. So almost a €50 million fine for 1g over the limit!’

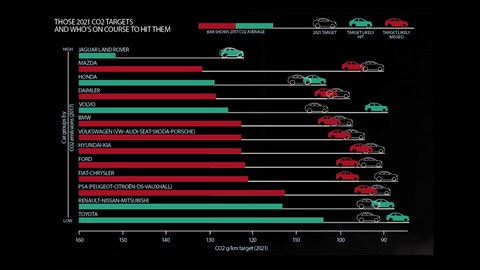

Clearly the bigger the miss, and the bigger the volume, the more a car maker will have to pay. PA Consulting has forecast the CO2 average in 2021 for Europe’s 13 biggest car groups, based on their projected sales mix, vehicle weights and electrification strategy (see graphic below). The consultants project that Ford and Fiat-Chrysler won’t hit their targets, calculating they face enormous fines equating to 10% of their 2017 global earnings. However, Ford of Europe president Stuart Rowley said ‘we will be compliant,’ speaking to CAR at the firm’s big electrified product announcement in early April 2019.

Volkswagen Group is staring down the barrel of a €1.4 billion penalty. As for Kia, ‘If we keep the sales mix as it is today, we will be 5g above the target,’ says Martins. ‘We have to increase the mix: we need to be 30% electrified by year-end 2020.’

As a result, the Korean brand is ramping up its electrified range. The pure-electric e-Niro – a midsize crossover with 282 miles of range for £32,995 – is on UK sale now, but in very limited quantities. A zero-emissions Soul will follow, while a mild hybrid system is available on the Sportage now, shaving tailpipe carbon by 4%.

Mild hybrid (HEV) will be rolled out across the Ceed family too. ‘But HEV will not fix the problem – you need to get into plug-in vehicles as well,’ warns Martins. Kia will launch 16 electrified products by 2025, including a hydrogen fuel-cell car.

How the EU 2021 CO2 limits work: the official European website

Why are car CO2 emissions going upwards?

In 2007, average CO2 emissions for new cars sold in Europe totalled 158.7g/km. It’s dropped by 16% this decade, but the figure is now going in the wrong direction again.

Two trends are to blame: the rise of the SUV, and the fall of the diesel engine. SUVs are taller, less aerodynamic and heavier than conventional cars, so emit more carbon. Concurrently, negative publicity for compression-ignition engines has led to a collapse in registrations.

VW is culpable for its emissions-test cheating, but politicians have exacerbated the situation with some blanket criticism of diesel particulate and nitrogen dioxide emissions, failing to point out the marked improvement in the latest engine tech. The flipside is that the more efficient diesel emits around 15-20% less CO2 than a petrol engine, so the slump in demand could not have come at a worse time as manufacturers scramble to hit their targets and the world worries about climate change.

VW emissions scandal explained

The financial pain beyond fines

Opel-Vauxhall is one of the biggest laggards on CO2, which wasn’t a big priority for its previous owner, General Motors. But now PSA Groupe is in charge an electric Corsa will be unveiled this year, with a battery-powered all-new Mokka X and zero-emissions Vivaro van following in 2020. Electrification can only happen once Vauxhall models switch to PSA architectures, so a plug-in Astra or Insignia will trail well behind the Peugeot 3008-based Grandland X PHEV, due in 2019.

Vauxhall’s Stephen Norman (below) has been given an average CO2 target to hit in the UK to help PSA meet its Europe-wide obligations, and the managing director is under no illusion that he will have to micro-manage supply to keep a lid on emissions.

‘If the demand we’re able to create for low-emission vehicles is below the [required] percentage of the predetermined mix, the consequence would be a limit to the number of vehicles we’re able to sell. If the amount of pure combustion engines goes up and we go beyond [our CO2 target], the financial penalty is so great the company cannot afford to take that risk.’

It’s an unenviable position for car makers, having to extend waiting lists or forbid customers from their choice of vehicle. And there’s a knock-on effect – if factories are forced to slow down, jobs may be at risk. ‘If you don’t have the powertrains, the only way to sell cars in Europe is to reduce your volumes,’ explains Kia’s Martins. ‘And if you reduce your volume, there’s an impact on production.’ The shockwave would travel across the value chain, with suppliers and dealers taking a hit too.

The economics of electrification

An electric Corsa looks to be a hard sell, given the supermini is a budget-conscious battleground and Vauxhall’s battery-powered flagship could conceivably cost £10,000 more than a mid-range VW Polo. Even at a high price point, Vauxhall will struggle for profit until battery costs come down. But the pressure will be on brands to price EVs competitively to hit their CO2 obligations, which could cause carnage for the bottom line.

The UK government’s plug-in car grant will become even more influential in convincing consumers on a lower budget to go green. But last November, the electric car subsidy was reduced from £4500 to £3500, and the £2500 inducement for plug-in hybrids abolished completely. It was a move that left Hyundai UK’s outgoing CEO Tony Whitehorn astonished, as the Ioniq EV became almost £2000 cheaper than the plug-in hybrid version. Whitehorn’s view is that it’s too soon to pull any funding for this nascent market – a logical point given that PHEVs are a gateway drug for pure electric cars, uncompromised by the range-anxiety issues that will hamper EVs until Britain’s charging infrastructure is bulletproof.

So the transformation of the European car fleet is going to accelerate markedly over the next few years. High-power, low-efficiency engines will become a hindrance, heavy SUVs may go out of favour, and mild hybrids will become the bare minimum on the road to pure electrification.

Volvo sewed up The Times’ front page in 2017 when it announced that, from this year, it will never launch another purely combustion-engined car. ‘This is for the customer,’ announced CEO Hakan Samuelsson. Partly. But it’s also to help Volvo defuse the CO2 timebomb of 2021 and beyond.

Further electric car reading

How much does it cost to charge an electric car?

The best plug-ins and PHEVs

How do hybrid cars work?