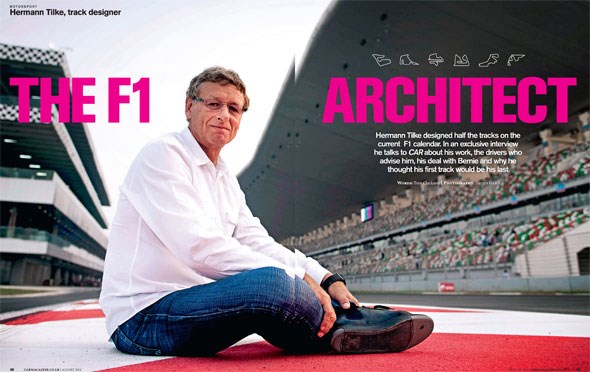

Is this man a genius? You have to hope so because he’s designed half the tracks on this year’s Formula One calendar; and cars, irrespective of their performance, are only as spectacular as the tracks around which they’re racing. Monaco is utterly captivating, Bahrain less so – you get the idea.

Hermann Tilke holds the key to much of F1’s modern-day magic. But how did this affable amateur racing driver become F1’s unofficial official track designer, and will he hold the position ad infinitum? He’s already penned 65 tracks around the world and there are more to come: he’s applying the finishing touches to Sochi, where the Russian Grand Prix will take place later this year, and work is well underway on new circuits in Azerbaijan and Mexico.

Let’s start with the good news: Tilke has the necessary qualifications to do the job. He’s not one of F1’s self-taught entrepreneurs; he graduated from Aachen University with a degree in civil engineering and he cut his teeth with a local company specialising in transport projects. He set up Tilke GmbH in 1983, and it was at about this time that he embarked on his racing career. He entered hillclimbs in his mother’s car – ‘she didn’t know; I said I needed to borrow the car for a few hours’ – and he progressed to touring cars in subsequent years, a highlight being the Nürburgring 24Hrs, in which he shared a car with F1 driver Alex Wurz.

After 10 more years working mostly on transport infrastructure, Tilke’s big break came in the mid-’90s, when his friend Franz Wurz (Alex’s father) got him the job to re-develop the Osterreichring. With a small budget and limited acreage, Tilke built the A1 Ring in just 240 days prior to it hosting the Austrian Grand Prix in 1997.

‘There was some criticism towards the track when it first opened,’ says Tilke. ‘A lot of drivers, including some high-profile ones like Damon Hill, said it was boring and there was a time when I thought I’d never be asked to do another track!’ But nothing could have been further from the truth. In many ways the A1 Ring was ahead of its time because it needed no modifications when F1 returned there (as the Red Bull Ring) this year after an 11-year hiatus. Better than that, many of F1’s new drivers said it was one of their favourite tracks.

The racing was good at the A1 Ring and the floodgates opened for Tilke. First up was some cosmetic work at the Nürburgring, which had just signed a new long-term deal with F1 tsar Bernie Ecclestone, and then there was his first government vanity project: Sepang.

The venue for the Malaysian Grand Prix needed to be more than just a racetrack; it was a statement of intent. Then Malaysian Prime Minister Tun Doktor Mahathir Bin Mohamad used the circuit to launch his ‘Vision 2020’ campaign, which focused on turning Malaysia into an industrialised nation.

In a very small period of time Tilke GmbH morphed from a specialist company of 18 people into a multi-faceted, multinational business employing 300 people. ‘Sepang was a big project,’ says Tilke. ‘They wanted to show that they were modernising and they wanted something that shouted “Malaysia”. That’s why we came up with the idea of lotus-leaf grandstands, but we always like to conceive dramatic architecture that reflects the host country.’

Many would argue that Sepang was one of Tilke’s best efforts. The races are usually exciting and the layout is challenging for drivers and engineers alike. But Tilke is reluctant to single it out ahead of another track, so let’s leave it to Fernando Alonso to outline Sepang’s strengths.

‘It’s very enjoyable to drive,’ says the two-time world champion. ‘There’s a good mix of corners, some of which have a late apex and require you to brake and turn at the same time, and the fast corners at 5 and 6 are really good. The change of direction is very fast there.’

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that Sepang is popular with drivers because several of them had an influence in its design. Former F1 driver Marc Surer gave his two penn’orth to Tilke, as did Michael Schumacher, who persuaded him to include the tight right-left at the end of the pit straight.

‘That sequence was thanks to Michael,’ says Tilke. ‘There was going to be a right-hander there, but he suggested the right-left sequence because it would give the car on the outside of Turn 1 a chance to fight back through 2.’ And that’s exactly what happens (and it was also something Schumacher was a specialist at).

However, for all the success of the Red Bull Ring and Sepang there have been some howlers from Tilke. Bahrain, Abu Dhabi and the new Hockenheim, which he re-profiled in 2002, raise questions about why F1 doesn’t have more than one pet architect. All three of these tracks lack character and they don’t punish mistakes due to excessive run-off areas – accusations that don’t apply to F1’s traditional heartland of Spa, Monza, Suzuka, Interlagos etc.

But is Tilke the culprit or the victim? Were his designs flawed or was the canvas upon which he was asked to work too limited? How can any track designer incorporate 2014- spec levels of safety and still expect a track to give drivers the danger rush that is so addictive?

Take the Yas Marina circuit in Abu Dhabi. Kimi Räikkönen describes it thus: ‘The first section is okay, the rest is a bit sh*t.’ And it wasn’t even good for overtaking, until the introduction of DRS in 2011. How did Tilke build such a lemon, given the financial resources available to him?

‘You need to remember that there are many different factors at play and we do the best job we can with what’s available,’ he says. ‘Many people ask me why my tracks have long straights in them. First, it’s good for F1. But circuits need to be successful all-year-round and when clients pay for track days they want to feel high speed. The easiest way for them to achieve that is down a long straight; that’s also why we do it.’

Whatever your opinion about Tilke’s tracks, you can’t argue with their levels of safety or their technical difficulty. They encourage close racing and some observers reckon the stunning battle between Nico Rosberg and Lewis Hamilton at this year’s Bahrain Grand Prix could only have taken place at a Tilke track because the layout lends itself to overtaking and the vast run-off areas encourage the drivers to have a go.

‘I think Tilke understands the demands of modern cars and modern F1,’ says former F1 driver Anthony Davidson. ‘The circuits are wide and the run-off areas are well thought out, and you can overtake because the long straights increase the length of the braking areas.’

‘The level of safety that Tilke incorporates in his tracks is impressive,’ says Jenson Button. ‘They’re all quite technical, so it’s difficult to nail a lap and that’s how it should be. They’re all quite different too, which is a surprise given that they’re done by the same guy.’

Tilke argues that his company’s only ‘design stamp’ is the long straights. Beyond that they’re all very different, which he says shouldn’t come as a surprise because of the number of people working on each project. ‘We have more than enough people to ensure we come up with original ideas,’ says Tilke. ‘The first person I speak to about each project is Bernie. He and I discuss it; then I discuss it with my business partner Peter Wahl, before opening it up to other people in the company. We put all of the ideas together and then choose a way forward.’

It’s a successful process because the tracks get designed and built quickly and, as a result, the jobs keep coming in from Ecclestone. Remarkably, there’s no contract between Tilke and Formula One Management; the commissions come on the back of a recommendation from Ecclestone. ‘The new places can use other people,’ says Bernie, ‘but I tell them that it’ll end up costing them more because Tilke has so much experience and he doesn’t make mistakes.’

Whether you love or loathe his work, Tilke has been an integral part of F1’s global expansion in the last 10 years. He’s turned a swamp on the outskirts of Shanghai into the Shanghai International Circuit; he’s broken with convention by introducing F1’s first night race in Singapore, and he’s now being rewarded for such vision with projects outside F1. He’s building hotels in Bahrain, hospitals in Abu Dhabi and even a football stadium in Germany (the 33,000-capacity Tivoli stadium, home to Alemannia Aachen).

There’s no other track designer on F1’s horizon, and there won’t be at least until Bernie moves on. Going forward, all we can do is hope for more Sepangs and fewer Yas Marinas.

Which is your favourite Tilke track? Click ‘Add your comment’ below and sound off