Not gonna crash this car. I am not going to crash this car. I am not going to have my most expensive and probably final accident at 30 bloody miles per hour. But not having the accident is easier said than done when I’m 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle, three days and 1200 miles into the craziest road trip a Bentley Azure will ever make, driving at night over steep, sheet-ice roads I struggle to stand up on, across which an Arctic gale is blowing powder snow so hard and fast that the headlights illuminate what looks like a weird white conveyor belt running at right angles over the road.

There are orange markers to show where the road is, or was, but I lose sight of them when the snowdrift blows higher. Sometimes it blows so hard and high that I lose sight of the flying ‘B’ at the end of the Bentley’s bonnet, so I just stop, and wait, and hope it stops before I get snowed in. Better that than leave the road and end up in one of the fjords these roads run high above. The next living being to set eyes on me would probably be a curious cod, nosing around the Azure’s dissolving hulk in a few years’ time, wondering why some idiot chose to drive so far north in such an unsuitable car.

You’re probably wondering the same thing. I did too, frequently. There probably are less suitable cars in which to drive north of the Arctic Circle, but I can’t think of one right now. The Bentley has almost everything you don’t want up here; a soft top, rear-wheel drive, 645lb ft of torque and five-and-a-half metres of hand-tooled coachwork. It also has a price tag of £222,000. I have driven more expensive cars, but not many, and never on ice.

Bentley has some balls making a convertible from the bones of the vast and antiquated Arnage saloon, fitting it with a twin-turbo version of an engine so ancient it’s mentioned in the Old Testament and charging nearly a quarter of a million quid for it. But it shows that Bentley can still do old-school, big-bore, double-barrelled British motoring alongside the more anodyne Continental.

And it will sell, mainly to rappers, oil sheikhs and superannuated, syphilitic Hollywood producers retired to Palm Springs. The great tragedy of the Azure is that these people will only ever use it as a boulevardier when it’s actually a half-decent car to drive. It’s an open Bentley with a truck’s torque, just like those ’20s Le Mans cars, but nobody will ever do anything remotely heroic in one.

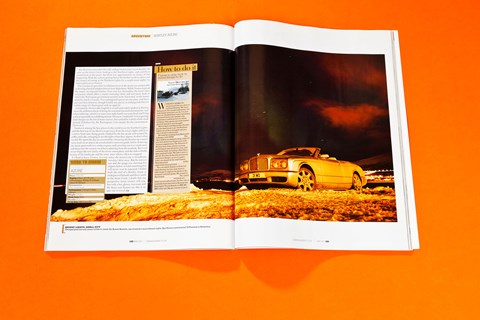

So we thought we would. We thought that the best thing you could look at through the open roof of the Azure was the Aurora Borealis, or the Northern Lights; the weird, ethereal, spectral glow created as particles borne from the sun on the solar wind collide with the earth’s upper atmosphere and create shifting clouds of green, purple and red. You need to get within around 1500 miles of the North Pole to see the Lights, and for us that meant a boat to Bergen and three long days of driving from the middle of Norway to the top.But the Lights are capricious; if terrestrial or solar weather conditions aren’t right, they won’t show. You might be able to buy the car but you can’t buy the view, and we always knew there was a chance we could do this whole trip and not see them once.

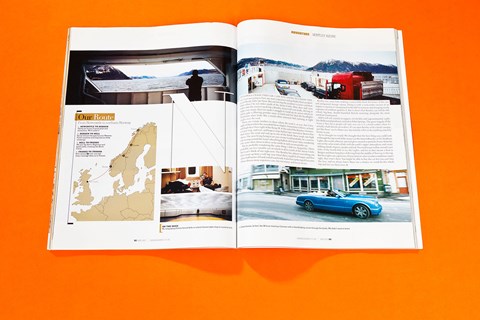

The 1300-mile route from Bergen, where our ship from Newcastle docked, to Tromso, the town in the very far north where we hoped we’d see the lights, uses just three roads. The E39 runs around the western fjords north of Bergen and covers some of the most spectacular of Norway’s 51,000 miles of coastline. At Trondheim it meets the E6, the Arctic Highway, which runs straight north, crossing the Arctic Circle before joining the E8 into Tromso. On your European road atlas they’re marked with the same thick line as the M1.

But any hopes we had of enjoying three-lane blacktop all the way faded about 20 miles into the trip when the E39 started climbing into the mountains, and dropped to one lane in each direction, and in places just one lane. Even the modest 450 miles we hoped to cover each day was looking ambitious.

There were rewards, of course. Immediately, the scenery was as good as anything Scotland can offer, with sheer rock mountainsides that fill the entire windscreen and force you to peer forward and up to see the peaks, unless you put the roof down, which rain was preventing. The temperature was still single figures above, but as we drove north the snow started coming further down the hillsides until it lay on the verges, but not yet on the surface. So we could nail the Bentley, using the turbos and torque to compress overtaking distances and dispatch slower traffic on the short straights, and aiming its square corners at the apex of each switchback and getting hard on the gas on the exit, making the whole nose sit up like the bow of a speedboat. For something so vast and unlikely-looking, the Azure handles. The carbonfibre beams added to the Arnage chassis beneath it mean the pillowy ride we enjoyed over Bergen’s cobbles is matched by an amazing accuracy through bends.

The Norwegians are unfailingly helpful, spotting you early, and indicating when it’s safe to overtake. It’s amazing how your attitude to other road users improves when you have to stop every hour or so to have a coffee with them aboard one of the six little ferries that cross the fjords too wide or deep for the E39 to bridge over or tunnel under.

We suspected that the Bentley wouldn’t be the fastest thing on the road for long, and we were right. We spent the night in Hell – you can insert your own bad pun – a little village near Trondheim, which turned out to be much colder than advertised. As we drove north on the E6 the needle on the temperature gauge set into the Azure’s walnut dash dipped under zero for the first time, and the snow and ice began to creep out from the verges and across the tarmac. I had to peg the speed back, which was a pity; the E39 and E6 were turning out to be the best driving roads you’ve never heard of. You don’t know what’s coming next; you might be snaking along a stretch cut into the hillside high over a fjord or a frozen lake; running fast and straight along a valley floor with imperious white peaks towering on either side; or barrelling between the six-foot white walls the snowploughs have to cut to find the road in places. And the roads can be unnervingly quiet.

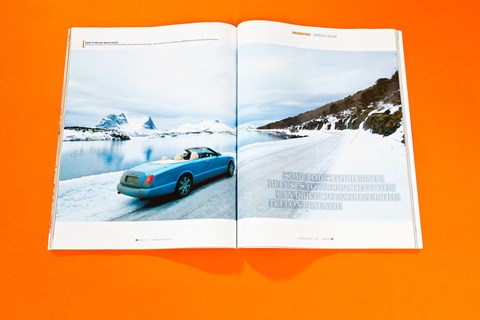

We’d forgotten about the Northern Lights by now; what you see from a northern Norwegian roadside in daylight alone repays your efforts. It is the most beautiful place I have ever been. It starts out alpine, then turns polar. It is stark, monochrome and alien. Much of the time you can only see three things: rock, water and snow; and three colours: blue, grey and white.

The feeling that you’re driving through a Tolkien novel is exaggerated by the place names; after Hell, we saw signs for Moan, Hammerfest and Orkanger. There’s something Mordor-ous about the long, narrow, rough-hewn rocky tunnels through the mountains, and the weird optical and climatic effects you get this far north. As well as the Northern Lights, there’s the midnight sun and the Fata Morgana, where the dry atmosphere and low temperatures combine to reflect images of the landscape onto places they couldn’t possibly be, like a mountain range on the sea horizon.

It’s inspiring, but deadly at the same time. You look at those vast white peaks and realise that man is simply not welcome there, but that you’re about to travel through them. You wonder why mankind came this far north in the first place; why, when homo erectus first emerged from Africa’s Rift Valley he didn’t just stop somewhere temperate and pleasant, like the south of France. You wonder how it must have been to cross this terrain without a well-heated, Wilton-and-walnut-lined Bentley; with only reindeer skins to keep you warm and, if you were lucky, a horse or a coracle for transport.

And you feel the despair of those who didn’t make it, from when this place was first settled in the Ice Age, to today. The Arctic Highway is also known as the Blodvei, or Blood Road; just north of where it crosses the Arctic Circle is the cemetery for 7000 mostly Russian and Serbian forced labourers brought here to build it for the occupying German army. While we were in Norway two British skiers died in bad weather a thousand miles south of where we were heading.

Before long the tarmac was gone for good, and we were in the kind of conditions that would bring Britain skidding to a halt. Punitive new car taxes mean flash metal is rare here; despite the conditions cars are made to last longer, and you see healthy, cared-for, Cold War-era kit that you would no longer find in a British scrapyard. Until you get very far north they don’t bother much with off-roaders. The Norwegian car of choice is an old Volvo, Merc or Audi estate, maybe all-wheel drive but always running dinner-plate foglamps, studded tyres and a roofbox for the skis, sides streaked with salt and being driven flat-out through a whiteout, powder snow billowing out behind it.

We hadn’t done much to prepare the Azure for this trip. I put my biggest steel jerry can in the boot, because when it’s 15 below and your car does under 15 to the gallon, believe me, happiness is a fully fuelled Bentley. More importantly we fitted proper winter tyres, which have a blockier tread to clear the snow and slashes cut into the blocks which sucker themselves to ice below.

The grip they produce is incredible, and you begin to learn just how far you can push three tonnes of Bentley on a surface you could skate on. The grip under braking is amazing, but you need to do it in a straight line; you really don’t want still to be shedding speed as you arrive at a corner. Then you hold the throttle ultra-steady and turn in; every time the front end just gripped instead of understeering into a snowbank I offered silent thanks to Thor, or whoever it is they worship up there.

The only things the tyres struggled with were the Bentley’s vast torque – the turbos were barely woken north of Hell – and slush. Slush is evil. White ice covered in compacted snow is like Arctic tarmac and we could do 70mph or more across it. Just because slush is soft and wet and brown you think it’s safer, but it destroys the car’s braking distances and directional stability, sometimes sending it into a terrifying slow shimmy that thankfully never got any worse.

The Azure’s revised ESP system generally intervened early and with subtlety; you can feel it taking control of the car and correcting its course the way your hand gripped a Matchbox model as a kid. You don’t appreciate how good stability control is until you need it, but in these conditions you don’t rely on it; there are some situations it just won’t save you in.

But confidence is the biggest factor limiting speed. When I had it, I started overtaking the locals again, easing the throttle open to accelerate over the ice without spinning out, before realising that the locals were probably travelling at that speed for a reason, and that I shouldn’t be so cocky. When it left me, I could be 30mph slower than I would be otherwise on the good ice. Sometimes your brain just refuses to accept that physics allows you to drive so fast in something this powerful, heavy and expensive over the Teflon beneath.

The Norwegians do not suffer such crises of confidence. I’d be amazed if there’s a country with a better standard of driving; stop a Norwegian to ask for directions and you expect to get it in pace notes. ‘Post office? Down to the end of the road, then left 60 over crest, don’t cut.’ The entire country seems to drive just beyond the available level of grip; we were overtaken at 70mph by a Volkswagen van whose driver calmly corrected a massive oversteer moment as he came off the gas. We tried to follow another in an Audi estate whose flickering tail-lamps told us he was left-foot braking into every bend.

We reached the Arctic circle late at night on the second day. At first it felt oddly anti-climactic; we were driving in a vicious blizzard, but had been for a while, and even under a canvas roof the Bentley’s cabin isolates you utterly from any unpleasantness outside. When the road is straight and the grip is good you relax a little and shift slightly in the excessively plump and smooth seat; you try to stretch your fingers right around the fat wheel; fiddle with the thick, chromed switchgear and almost forget what you’re driving through.

The circle itself is marked only by two telegraph poles on either side of the road and a visitor centre, which visitors might find hard to spot under an eight-foot snowdrift. It was only when we got out to take our pictures that we realised what the Bentley’s impressive hood had been sheltering us from. The dial was reading ‘only’ minus 10, but what we didn’t know until we drove back south in daylight was that we were standing in the middle of a high, flat icefield across which an Arctic gale was blowing.

Any exposed flesh just starts to hurt; it doesn’t have time to start to feel cold. We were well kitted-out, but even sheltering in the open door of the Bentley my hands started to ache and cramp in the minute I spent gloveless changing the batteries in my Maglite.

And then we saw it. At first you might think it’s a cloud or just another mountainside. But then you notice that it’s actually a pale green, and is slowly shifting into shapes no cloud could form; arches, pillars, funnels and curtains. Suddenly you forget about the cold; no matter how rational, modern and urban you are, the Northern Lights make you surrender to the Neanderthal urge to stand and stare and point in dumbstruck wonder at something inexplicable in the sky.

But then you remember the cold, and get back in your warm Bentley. We were on the Arctic Circle, looking at the Northern Lights, and could have turned back at this point. But there was approximately no chance of that happening. With the scenery getting better the further north we drove and the chance of staring at the Northern Lights for a couple more nights, we had to press on to Tromso.

The reaction we got when we slid into town in the Azure was comparable to droving a herd of reindeer down Crewe High Street. While Tromso enjoyed the Azure, we enjoyed Tromso. First stop was Arctandria, the town’s best restaurant, which offers a starter featuring whale and seal meat, both of which the Norwegian government permits to be ‘harvested’, to the horror of pretty much everyone. Two endangered species on one plate, and that’s just your hors d’oeuvre, though frankly any species is endangered when it’s within range of a Norwegian with an appetite.

Fortunately, the fact that English is so well and widely spoken in Norway saves the embarrassment of doing the standard international mime for ‘seal’ when ordering, which is to raise your right hand over your head and bring it down repeatedly in a clubbing motion. Of course, I ordered it. I was expecting dodo-burger on the list of main courses, but settled for a thick whale steak instead. Fabulous lot, the Norwegians. Care deeply for the environment. Then eat it.

Tromso is among the best places in the world to see the Northern Lights, and the best way to see them is to get away from the town’s lights and sit in a native Sami tent, being gently smoked by the fire inside and warmed by coffee and cake, emerging to see the lights when they appear. So that’s what we did. We spent the day on snowmobiles, bouncing the Bentley up a rutted snow track on an almost-deserted island to meet our guide, before shattering the Arctic quiet with two-stroke engines and careering out over virgin snow and deep into the scenery we’d been admiring from the roadside. But I will never forget the raw clarity of the Arctic atmosphere and the indescribable beauty of the landscape and the utter, utter silence when we stopped.

It’s hard to leave Tromso. In every sense; the nearest city is Trondheim, two days’ drive away. But the sun was out and the gauge was showing five degrees below, so I did something that will never, ever be repeated: I folded back the roof of a Bentley Azure at 69 degrees of latitude and drove south to the Arctic Circle. I doubt that any prospective Azure owners will care, but with a hat, gloves, two coats and the fierce seat heaters on, this is an epic way to travel.