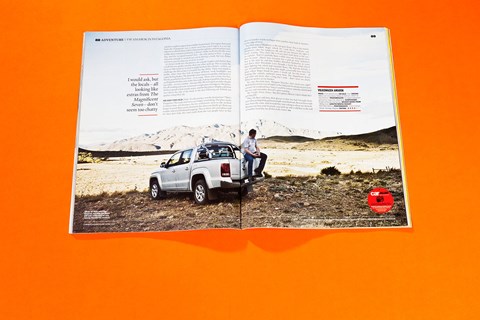

I don’t know why I thought this was a good idea. I’m standing on a tonne of timber piled, unsecured, into the back of a Volkswagen Amarok with the tailgate down, and I’m clinging to its fat chrome roll bar because beneath me the truck is bellowing and bucking over soft sand and thick clumps of brush as it climbs a 45-degree mountainside, sending me, the two blokes standing next to me and the timber bouncing wildly. We’re either going straight up, making the timber start to slide out the back, or straight across; our direction decided mostly by which way the front wheels land each time they rear up. Straight across is scarier. This is what made me climb out of the cabin and stand in the back; if we barrel-roll down the mountainside I thought I’d rather try to leap off the side than get stuck in the cab.

But now I’m not so sure I’d be able to leap clear of a fast-rolling truck and 40 thick eucalyptus fence posts. This is easily the most dangerous thing I have ever done in a vehicle, and very possibly the last.

Patagonia is pick-up country. The gaucho cowboys and ranchero farm owners who work the vast arid steppe of southern Argentina have – mostly – swapped their horse for a HiLux. The ranches down here are called estancias, and pick-ups are called estancieras (‘the lady of the ranch’), but they don’t get treated like ladies. As part of its plan to be the world’s biggest carmaker Volkswagen is making its first proper, one-tonne pick-up; the Amarok takes direct aim at the famously indestructible Toyota HiLux and is built in Argentina. So we thought we’d give one to the gauchos to see if they could break it. And if they didn’t, we’d use it to explore this empty, epic landscape.

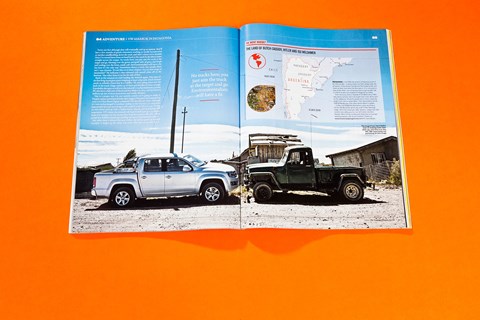

Our ranchero is, somewhat disappointingly, called Alastair Whewell. His dad is from Manchester and his mum’s from Oxford but Alastair is the real deal. His old man, Roger, shipped a Land Rover to Colombia in the late ’60s and over a decade and 250,000 miles of driving made his way south to Patagonia, climbing South America’s mountains – some of them never before conquered – as he went. When he got here he rebuilt the Land Rover’s engine with a stock of old parts he found in a crate in a general store, and decided to stay. He bought the 25,000-acre Fortin Chacabuco ranch, and Alastair and his brothers were born here.

In fact, they’re the typical Patagonian family: immigrants attempting to earn a living from this unforgiving land. Alastair is fully Patagonian; he speaks English with an odd Spanish-Mancunian accent and he shares the Patagonian look and attitude with everyone else who lives here. Whether European, indigenous Mapuche, or Mestizo mix, they all have a certain leatheriness of skin from the fierce, fast winds, eyes narrowed by the intense, ultraviolet sunlight (even the sheep get sunburnt down here) a steely self-sufficiency and complete contempt for Argentina’s politicians.

Alastair also typifies Patagonians’ dependence on pick-ups, and drives a battered ’66 Ford. ‘The stuff I’ve done in that truck,’ he shakes his head. ‘When times were tough here and we had to hunt deer just to eat in winter I had 15 females piled in the back. We had to cut our way through the snow and ice to get out and back. It looks like shit but it’s never let me down.’ His four-year-old son, Valentino, is learning to drive in it, but there’s no sentiment. I get the feeling that, like a horse, if it went lame, he’d shoot it.

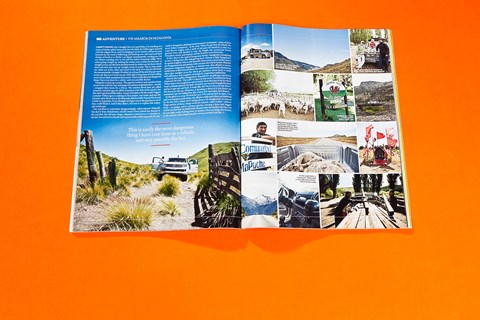

So the plan is to swap ’66 Ford for 2010 VW, and see how it copes. First task is to transport some sheep. My efforts to help catch them are inhibited by the fact that I think we’re taking them to be slaughtered, so instead Diego catches all three. Diego works for Alastair, refers to him – without irony – as gringo, and is a proper gaucho, wearing a beret and dagger tucked into his belt. Its blade looks sharper than his intellect but boy can he can rugby-tackle bolting ewes. In minutes three are lying, feet bound, in the Amarok, defecating furiously over our pristine load bay.

Turns out that although they will eventually end up as mutton, they’ll have a few months of gentle retirement working as woolly lawnmowers at another smallholding down the road, and that’s where we’re headed. Once I’ve turned them loose we head back to the ranch by the direct route: straight across the steppe. No tracks here; you just aim the truck at the target and go, blasting over the green and gold tufts of grass and brush and surfing over the loose, sandy soil. Environmentalists will have a fit, but here it’s the only way. ‘Sometimes there’s a track, but usually there isn’t,’ says Alastair. ‘It’s not like we’re short of grass. You see that range of mountains?’ He indicates a dun-coloured rock massif miles off on the horizon. ‘Our other fence is on the far side of that.’

Back at the estancia we start loading the Amarok again. This time it’s six-foot long eucalyptus posts weighing at least 25kg each, which Alastair needs to rebuild a fence lost in a wildfire. We start piling them into the back of the truck: Diego counts 47 of them and decides we have enough. It probably also puts us well over the Amarok’s 1147kg maximum payload. We also have a full tank of diesel and five blokes to carry, and the fence is halfway up one of those mountains and totally off-piste.

This is a proper test; I’m not entirely certain we’re going to make it. Despite square-jawed good looks that suggest V8 power the Amarok has only a two-litre diesel engine compared with the HiLux’s three, although it’s twin-turbocharged to produce 163bhp to the Toyota’s 171, and more importantly has way more torque with 295lb ft to the HiLux’s 253. It’s also an old-school pick-up with a ladder-frame chassis and leaf-spring rear suspension. VW claims the Amarok will haul its full load up a 45-degree slope; if it’s going to be the success they hope for in places like this, where people buy millions of pick-ups and flog ’em hard, it had better be able to.

But other than a distinct flat-spot before the turbos spool up around 1500rpm, it surges up the steep, soft tracks that take us up into the hills. You can choose either permanent 4Motion four-wheel drive with a variable torque split, or the selectable system fitted to ours, which offers rear- or four-wheel drive and a low-range transfer case. You can shift on the fly, and we don’t need the low range until we’ve left the track and are headed straight up the slope towards the fence line.

Even then the Amarok keeps going; the problem is our lax approach to loading. On side slopes the posts all try to roll downhill, piling up against one side of the load bay and bringing the truck even closer to tipping over, and when we go straight up they try to slide straight out the back. We stop every few dozen yards to drop a few more off, but when Alastair gets hard on the gas to bounce over a particularly big tuft the Amarok rears up and the remaining half-tonne goes shooting out the back, and it’s only by jumping up that Diego and I avoid getting dumped out with it. Diego bangs on the roof to tell Alastair we’ve gone as far as we can. We don’t bother putting it back on; the fencers can shift it by hand.

Inside, Alastair wipes the sweat from his face. ‘Shit, that was a test.’ He seems genuinely impressed. ‘I could never have done that in the Ford. I was going to have to bring that timber up here by horse. I don’t think 99.9% of the people who buy this thing will ever do anything like that. Just don’t tell the people who own it what you did in it.’ I don’t think we can hide it; the back is full of sheep shit, we’ve cracked a tail-lamp, torn off a mud-flap and have a puncture.

Alastair and Roger ask us where we plan to go next. We tell them we’re planning a long loop through the steppe, using two of Argentina’s most famous roads; the Ruta 40, which will take you from one end of this seemingly endless country to the other, if you have a spare month, and the Ruta 23, an almost entirely unmade road that runs from here, near the Chilean border, all the way east to the ocean.

Along the way we’ll pass through a couple of remote gaucho towns seldom visited by outsiders. Roger knows one of them. ‘Ha! That’s where I found those Land Rover parts. I haven’t been there in decades. You should see if that general store is still there. You’ll love it. It’s the kind of place that has a brassiere hanging up next to a camshaft.’

Alastair isn’t so sure. ‘It’s the Wild West out there. If they don’t like you, they’ll just stab you.’

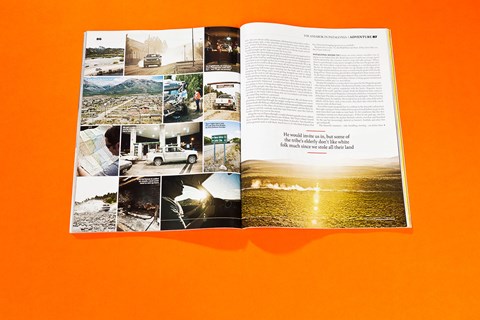

Patagonia seems to feature on every serious traveller’s list of places to see before they die. Road-trip across it and your average speed will be dented by the constant need to stop and take pictures. Where there is a paved road, it runs arrow-straight over the vast, flat glacial valley floors, the twin yellow central lines converging at a vanishing point in the far, far distance. Bare brown hills rise up sharply at the edge of the flat steppe and beyond them are snow-covered volcanic peaks of the Pacific Ring of Fire. There are long, glacial lakes whipped into three-metre swells by the fierce winds, iron and copper deposits that stain the mountainsides red and blue, and condors and turkey vultures circling against weird cloud formations unlike any I’ve seen before.

Despite the emptiness it seems there’s no space for the Mapuche people, who replaced the Tehuelche. The Benetton family owns millions of acres of land here and is pretty unpopular with the locals; Mapuche means ‘people of the earth’ and they simply think the Benettons have stolen it. We stop to visit a small Mapuche community which has ‘reclaimed’ some of the land. The elder we speak to is friendly but apologetic. They’re having a birthday party, he explains. He would invite us in, but some of the tribe’s elderly will be there, and, in his words, they don’t like white folks much since we stole all their land.

Few of the roads are paved, but it’s a tribute to the Amarok’s refinement that signs saying we have 100km of loose gravel track before we get to the next town don’t just make us turn back. It’s for conditions like this that carmakers torture-test their prototypes. If they’re not pick-ups, the few cars we meet tend to be ancient Renault saloons, rust-free and bleached by the sun but increasingly skeletal as bonnets, bootlids and other bits get rattled off.

The Amarok’s manners – ride, handling, steering – are better than you have a right to expect from a ladder-framed truck. The engine, borrowed from the Transporter van, is more vocal than you’d expect in a car but otherwise refined; there’s little vibration through the control surfaces and, unlike most commercial diesels, it doesn’t shake itself into life like a wet dog. And the six-speed manual ’box – the only option at first – is great; muscular enough to remind you you’re driving a truck, but way slicker and more precise than any rival we’ve tried.

It’s better inside too: the plastics are a grade tougher and shinier than a Golf but two grades smarter than any other pick-up. This is easily the most car-like truck we’ve tried; it might not have the volumes – at first – to challenge the HiLux but it certainly has the ability. There isn’t much to dislike, other than that lack of torque off-boost, weak headlights and vague-feeling brakes. The Amarok’s most impressive quality, and one we’re bloody grateful for down here – is its range. There aren’t many two-litre, 34.8mpg diesels that carry an 80-litre tank, making it good for a theoretical 640 miles – or over 1000km – between fills. We managed 500 miles despite the off-roading and some sustained 100mph-plus running over the plains. At these speeds it feels utterly secure, and the big mirrors display a glorious view down the side of the truck to the dust billowing out behind you against a deep blue sky.

Heard the old cliché, ‘it’s the journey, not the destination’? That’s Patagonia. The roads and views are simply astonishing. The place seems to distort time and distance; the few settlements seem to take an hour longer to reach than you’d calculated, but when you finally get there you wonder why you’d bothered stopping. They’re dusty, dirt-poor places and it’s clear how little this land yields from the way people have to live; often in wooden shacks no bigger than a garden shed, built in shanties on the edge of town.

Our final stop is Pilcaniyeu, as the sun goes down. This is the remote gaucho town where Roger rebuilt his Land Rover. Federico, our interpreter, takes his sunglasses off, and not just because the light is finally waning. ‘They don’t like it if you don’t look them in the eye,’ he explains. ‘And it’s probably been a while since any Europeans have been in town.’ (Down here everyone has a pick-up story: Federico’s best is the time he and four buddies drenched themselves in water and drove their Mitsubishi L200 through a brush fire which they’d been fighting but which had encircled them.) We find the boliche, a

sort of combined bar and shop that might conceivably have been the place where Roger found his parts. I would ask, but the locals – all looking like entirely authentic extras from The Magnificent Seven, and tired and dusty after a long day’s work – don’t seem too chatty.

What we need is an ice-breaker.

‘So,’ says the main man, ‘Margaret Thatcher. She’s dead now, right?’ With fresh tension over oil rights in the Falklands breaking out just as we arrived, I’d wondered how long it would be before someone mentioned the war, and remember Alastair’s grim warning.

‘No,’ I reply. Stony silence. ‘But she’s pretty old now. I don’t think she’s got long left.’

They all cheer and raise their glasses to that; but had I brought them news that an Argentine politician might soon check out, the reaction would have been the same. And instead they start asking us about our Amarok, because out here your livestock, your pick-up and a cold beer at the end of another hard day are all that really matter.