► McLaren’s historic car paradise

► Inside Unit 2 storage mecca

► Like Area 51 for Formula 1

McLaren is considering mortgaging its extensive F1 collection of historic racers and glamorous Woking headquarters to raise funds to see it through the coronavirus crisis, it emerged today.

Like all car makers, the McLaren Group has been hit hard as sales dried up, production seized and advertisers pulled back from its motorsport activities. Raising funds from its crown jewels – the rich archives of famous race cars residing in storage around Woking – is one of the options on the table. Sky News, which broke the story, claims it’s in talks with financiers to raise up to £275 million.

A spokesman confirmed to the BBC that it was ‘exploring funding options’ to temporarily raise capital. The financial shock follows an 18% jump in group revenues last year to £1.4 billion, but today some of the 4000 staff are furloughed and bosses are keen to inject more cash into the business to keep it afloat.

Read on for an archive gem, when we sent CAR contributor Ben Oliver deep inside Unit 2, where some of the most famous cars are kept. These are the extraordinary assets that could be mortgaged off to raise funds…

Inside McLaren Unit 2: an archive gem from CAR magazine December 2011

McLaren people refer to it as Unit 2. It is the polar opposite of their extraordinary, Space Odyssey McLaren Technical Centre headquarters in Woking, with its glass walls and cooling lake and famous architect and unnerving clinical sterility. Instead, Unit 2 is a low, 1980s, brick-built former factory on an industrial estate. I’ve been asked not to tell you where it is, or to show you its exterior. But if you wanted to find it, a photograph wouldn’t help you much. It looks anonymous and pedestrian and just like countless other industrial units across the country. Unlike the MTC, Unit 2 hasn’t been designed to impress anyone. In fact, nobody is really supposed to come here at all.

When Ron Dennis took control of McLaren in 1981 he decreed that none of his new breed of MP4 Formula One cars would be sold on the open market, although a handful have been slipped out by private treaty. Previously, McLaren had just sold off any remaining F1 and Can-Am and Indy cars at the end of each season, as most constructors did. In less rule-bound times, big F1 teams were building ten cars each season, so McLaren had to do something with those that weren’t crashed or cannibalised by the final race.

Since 1997 they’ve been stored here, wherever ‘here’ is. A few have been lent to museums or displayed on the long ‘boulevard’ that forms the spine of the MTC, and they occasionally emerge blinking into the sunlight at events like the Goodwood Festival of Speed. But mostly, one of the world’s most important, most valuable car collections is kept locked away in this old factory, and nobody ever gets to see it. As far as anyone at McLaren can remember, access has only ever been granted twice before CAR arrives; once to film a clip to be shown at the FIA’s end-of-season party last year, and again for a short film in which Lewis and Jenson meet Ayrton Senna’s 1988 championship-winning MP4/4, and which you can watch on YouTube.

Security issues aside, you can see why Ron doesn’t want to throw the doors open. The place that houses McLaren’s entire post-’81 back-catalogue isn’t very McLaren. There’s a tiny plaque with an outdated McLaren logo by the single front door, which opens into an industrial anteroom with a chipped, painted floor, a random jumble of dusty stacking chairs (Dust? At McLaren?) and a door to the gents’ with its long row of now-unused urinals, a legacy of the place’s factory origins. The main building is split in two. One half, to the left, is storage for the F1 team. But to the right is what you really want to see: a 30-year compendium of the work of one of the world’s greatest sporting teams.

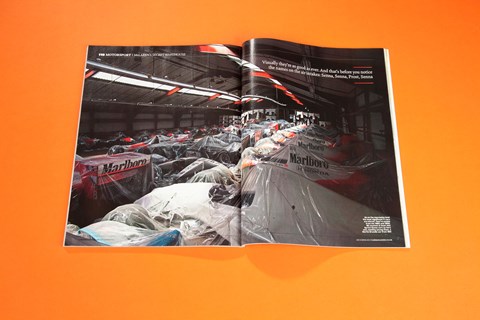

How do I start to describe it? Maybe with the intangibles. The atmosphere is utterly eerie. The McLaren staffer accompanying me excuses himself to let a colleague in and I’m left entirely alone. It isn’t huge in here: there’s maybe eight or nine thousand square feet of floor space, so it isn’t much bigger than a tennis or basketball court, but racking means huge flight cases and complete cars can be stacked three or four high, and there’s a mezzanine level up some steel stairs at the back where the cars are all on one level. That’s where I go first. I count 38 cars up here, mostly complete, other than their nose-wing sections which are removed and hung on the walls to avoid damage and make the cars easier to move.

Not that they’re moved much. The place is oddly, weirdly still, and the shafts of light from the glass panes in the roof show the dust in the air and make the polythene sheets covering each car look like ghostly shrouds. F1 cars aren’t meant to be quiet and still; the contrast between this place’s graveyard calm and the noise and kinetic energy that 38 F1 cars ought to emit is so great that you find yourself playing their soundtrack in your head to compensate. Visually they’re as good as ever when you lift a corner of the plastic: short and fat-tyred and mostly in that genuinely iconic orangey-red-and-white Marlboro livery. And that’s before you notice the names on the sides of the air intakes: Senna, Senna, Senna, Senna, Prost, Senna, Senna.

And after the stillness, the next thing you notice is the almost overwhelming – and, I promise, uncharacteristic – urge to steal something small from the open boxes of parts. Just a wheel nut, or a spare switch; something Senna might have flicked. They wouldn’t miss one, surely? I didn’t, Ron, if you’re reading this, because I know the sanctions are pretty severe for anyone who does. McLaren is a lean operation. It could buy or rent the space to store everything its F1 team makes, but that wouldn’t be the McLaren way. Instead, just one complete car is now kept to represent each season, with a stock of parts to keep it running. Other, older cars, the ones with less historical significance or that were uncompetitive (including Nigel Mansell’s) get ‘reduced’, a euphemism for broken up, so they can be stored more space-efficiently, their fuselages standing on their ends like chimney stacks. Enough parts are kept to reassemble them but everything else is culled. And instead of being auctioned off or sneaked out by employees or given away to fans who’d swap a testicle for the stuff McLaren thinks is superfluous, a specialist secure waste-disposal firm is called in to grind it up.

At least some of the oddball stuff gets kept. Lying on a flight case are what look like two jet packs, but are actually the cooling units for a chilled suit designed for McLaren’s pit crews. One of Lewis’s McLaren-built karts stands on its rear end next to the Senna cars. At the back of some double-depth, triple-deck racking, behind various race and road-going McLaren F1s and covered with a shroud, is the unmistakable shape of a Porsche 911; possibly the fastest 911 ever made. Porsche developed the TAG Turbo engines used by McLaren in the mid-’80s. Porsche was just a contractor, so when the project ended everything was returned to McLaren. Some of those parts could be sold off because they weren’t McLaren built or badged, but they kept the 911 in which Porsche tested the engines. Those engines had 1100bhp in qualifying trim by the end of their life. Yes, I did ask. No, they wouldn’t. But I’ll keep trying.

And it’s good to see that the ruthless McLaren machine can get caught out. Along one metal gantry are ranged the pit jacks designed to fit each car; elsewhere are the starter units needed to get them running. But they realised recently that the software needed to tune some of the engines wouldn’t run on modern laptops, so mighty McLaren went onto Ebay and started buying up beige, slab-like ‘heritage’ computers; there is now a pile of them in an upstairs office.

At its fullest, Unit 2 held 75 complete cars. But it is down to around 55 now, and will have just 40 by the end of the year. Ron isn’t putting them all in the crusher. They’re being drained of any remaining fluids, having their tyres pumped up and are being dispatched to the dealerships selling McLaren’s new MP4-12C, each of which will have at least one genuine Formula One car on display; not one of the plastic replicas you see in airport departure lounges and at sponsors’ events, but one that bites. Lewis’s ’08 championship-winning car already hangs over the entrance to the Hyde Park dealership.

Formula One is a famously unsentimental sport, obsessed with the next thing, not the last thing. We should be grateful that Ron kept the cars at all, and he’s probably glad he’s found a use for some of them. But I worry a little for those that remain in Unit 2, each a little colder, lonelier and dustier. As the door swings shut behind me, I wonder how long it will be before it opens again.