► Join us on a tour of Europe’s most efficient car factory

► Two cars roll off the production line every single minute

► Tour the home of the Qashqai, Q30 and more

As one of the most efficient car plants in the world, Nissan Sunderland builds half a million Qashqais, Jukes, Notes, Leafs and now Infiniti Q30s a year, at such a speed that raw material is turned into a car in less than a day. Extrapolate Henry Ford’s eureka moment forward through a century of technological progress and you wind up here, in a cathedral of manufacturing in which men, women and robots create 115 cars an hour in a heavy metal ballet of collaborative effort.

19.00 Under pressure

Boom! The oily metal grating beneath my feet trembles at the deep concussion. Boom! Another one before the air can still itself. Every four seconds: boom! The presses – three storeys tall, their foundations dug into the Sunderland rock three storeys down – beat two huge four-tonne dies together as they stamp out shapes in flat steel; a percussive soundtrack to which the rest of the plant must work. Welcome to the press shop.

If, like me, you think of car plants as pristine laboratories in which robots dance over shining metal skeletons in near silence, then the heavy industry of the press shop comes as a bit of a shock. Five storeys high and 165 metres long by 165 metres wide, the shop houses seven presses sitting alongside each othe like a herd of oblong metal dinosaurs, each as big as a house, busily munching through metal.

Every day, all day, at least a dozen lorries deposit rolls of steel 6ft high and up to 18 tonnes in weight, constantly feeding this beast of a factory. More than 1.7 million panels are punched into existence here each month, the presses bearing down on them with a force the equivalent to 40 tonnes.

21.00 Bodies beautiful

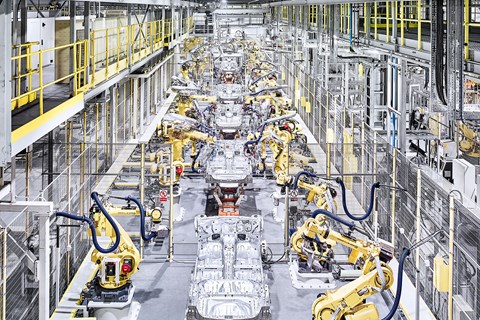

After the brutality of the presses, the Infiniti body shop is like stepping from the dark satanic mills of Victorian invention to the gleaming computer age. Bright, airy and quiet, the newest part of the plant exists to create Q30 bodyshells. The investment in integrating the new Infiniti into the existing industrial ecosystem? A cool £250 million.

In an hour, 15 Q30s each with 4300 welds (20% more than a Nissan Qashqai) are built by a legion of 141 robots, overseen by just 10 workers – the best of the best, handpicked off the Nissan line, Top Gun style, to ensure these cars meet the loftiest of standards.

A robot working on doors can complete 88 laser welds in 40 seconds. Done the old-fashioned way the same work would take four minutes. Accuracy and consistency are beyond even the most skilled homo sapiens, with class five lasers and guidance systems – the same level of kit Apache attack helicopters use to ensure they hit insurgents and not marines – bringing the precision.

Halfway around the body assembly loop is the framing station, where the platform meets the car’s side and roof frames. This is a crucial moment in the process – any inaccuracy here would compromise every subsequent production process, right down the line. Lasers check the robots’ work, cross-referencing in fractions of a second to the specified ideal and failing to see the funny side of tolerances exceeding fractions of a millimetre.

So striking is the level of calm, fuss-free automation in here that people seem almost redundant. ‘The robots are incredible at doing what is programmed within their parameters, but naturally they can’t adapt,’ explains Richard Scott, production senior supervisor. ‘They are far faster and more efficient than a person, so long as the parts are presented to them perfectly. If a part isn’t on the carrier in perfect position, they can’t make a judgement to move it around to the ideal spot. Thecost of building robots that can do that kind of thinking would be prohibitive.’

While some of the myriad parts each car requires come in from suppliers, and might have been on site for three months at most, the vast majority are made on site, and within a few hours. Richard explains: ‘The plant is mainly self-sufficient, with most sub-assembled parts built by suppliers either on site or within a few miles. Lead times are short; sometimes 24 hours. The plant employs 6700 people but the chain involves some 27,000.’

Sometimes the longer elements of the supply chain throw a link though… ‘We had a storm out in the North Sea and a ship carrying essential components couldn’t get into port,’ says Richard. ‘We contacted RAF Catterick and asked them if they needed any air-sea rescue practice. They picked some parts up for us from the deck of the ship; we paid for the fuel.’

23.00 Monochrome to colour

The paint shop is a timely reminder that producing cars is a dirty, hard-nosed business. I walk into a tunnel of air that scours me of dust and lint, and expect to emerge in another lab-like environment. Instead it’s like I’ve stumbled into a nuclear accident on a claustrophobic Cold War submarine, all low ceilings, throbbing generators, endless clanking, thick piping and the stench of industrial chemicals. Behind thick safety glass, men in full hazmat suits are silhouetted against arc lighting as they work, ghostly shapes cleaning, hosing and painting as the cars pass by.

With the Q30 new robots, dressed oddly in white protective gowns, have been installed that can recognise the body shape and paint

accordingly. The result is a much finer finish because, unlike the old tunnel sprayers, the Infiniti robots maintain a consistent distance to the body as they move.

Some 27 litres of paint are required to finish the various coats on each car – annually the Sunderland plant uses enough paint to fill six Olympic swimming pools.

09.00 The swarm goes to work

Ten hours after the cars enter the paint shop, they are dry and heading for trim and chassis. Above the workers – more than 3600 of them on a three-shift rotation – screens keep track and inform on ‘jobs (cars) per hour’ progress; essentially the plant’s efficiency. It’s running at 85.54% at the moment – not good in a plant that operates at 95% almost all the time, and aims to hit 98% next year. (100% is 60 cars an hour). ‘Sod’s law with you here,’ laughs my minder.

You believe him. Before the Q30 was added to the 945-metre production line, the Juke and Note went through 134 stages of build (Qashqai and Leaf are built on the line next door), with each station and the 224 operators allowed 1.066 minutes to complete their task. The result is 54 ‘jobs’ on each line every hour.

I watch the guys on the line, mesmerised. Incessantly, the cars keep coming from a dark hole in the roof and, wiry and lean, they slip through apertures and out again like eels on a shipwreck, picking up tools and parts, a pop and a quick whirr and then back and onto the next one. Nobody looks around for a screwdriver, asks Dave if he’s had the wrench or ends up crawling on their hands and knees, swearing and looking for a dropped screw.

It feels like if the lights went out, these guys could carry on regardless, hands moving instinctively to places for tools and parts as they have thousands of times, muscle memory and fine motor skills honed to millimetric precision at high speed. The robots of the body shop are impressive, but they have nothing on the line.

Everywhere you go, people talk with fervour about Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) and not passing problems on. It’s an almost monastic devotion to duty, and any issue found further down the line will be traced back to source, at which point the glare and opprobrium of thousands of Mackems and Geordies will be directed at the culprit – not a good place to be, for the passion for what happens here runs at a pitch only bested at St James’s Park and the Stadium of Light.

Anyone not adhering to the SOPs risks throwing the system out of kilter, and throwing it off even by the smallest margin creates vast problems when scaled up over thousands of cars. Tiny actions, huge consequences; every person vital yet subsumed into the greater whole. But while the way of doing things must be slavishly followed, it is not dogmatic. Kaizen, the Japanese concept of continuous improvement, means any worker who thinks they can do something better can pitch the idea. It will be analysed and, if found to be an improvement, implemented. Just don’t freestyle…

13.00 Testing times

After three hours and seven minutes in trim and chassis, the cars can move under their own steam, and go through an hour of testing, while the Infinitis head off for special treatment with a computer that runs all the systems on the car remotely to ensure there are no issues. Then there’s a 15-minute outdoor road test on the test track.

Every hour, 24 hours a day, six days a week, finished cars are loaded onto an endless stream of lorries and, 20 minutes later, unloaded at the Port of Tyne, ready to roll onto ships. The plant exports 80% of its half a million production units to more than 130 markets worldwide, while one in three of all British cars are built here. One in three. Even Henry Ford would be impressed with that.

Four seconds: The difference between Nissan and Infiniti

At station 34 a Q30 cockpit module (dashboard to you and I) is swung into place through the passenger door and the hydraulic lifter used to get it there is then pulled away. But it takes the worker two tugs to free it. Senior supervisor Jim Cambell and senior engineer Rory McCrystal watch like hawks – they don’t miss a thing, and exchange knowing looks and raised eyebrows. Half a second is being wasted. ‘It’ll be sorted,’ Jim states.

The Q30 line is in the process of being ramped-up to full production speed, and when the system was first introduced, getting the bolts to line up and the carrier away was taking even longer.

‘Because it’s a premium car, it needs more time spent on it than a volume car,’ says Jim. ‘So on some stations we’ve allowed three or four more seconds per job.’ Three or four? I do my best not to scoff.

‘To these guys, three or four seconds is an age. They work so quickly that those extra seconds allow them to really ensure quality is first class.’

Each Q30 has a robotised kitbox which rolls alongside the car and contains everything the workers will need for that particular build – more efficient than the old way of having pick parts out from cages next to the line, which in turn saves five steps, and buys the line those premium seconds.

Five car plants that aren’t Nissan Sunderland

Wolfsburg, Germany

The most famous super plant, with more than 800,000 Golfs and mid-size VW fare produced annually on the near three-square-mile site, which has two power stations and 50 miles of train tracks. Famously rescued from oblivion by the British army after the war, Wolfsburg claims to be the biggest car plant in the world.

Ulsan, South Korea

Even Wolfsburg is dwarved by Ulsan, which builds 1.5 million cars a year – the equivalent of one every 20 seconds, thanks to 34,000 workers and berths where three 50,000 tonne ships can anchor simultaneously.

Tesla, California

One of the world’s most advanced factories, containing 5.3 million square feet of manufacturing and office space. 100,000 electric vehicles a year are built on its heavily robotised line.

Piquette Avenue, Detroit

Although Highland Park is the birthplace of the moving assembly line, Piquette Avenue was the original home of Model T production from 1908. Twelve rolled off the line in October, 200 by December and in 15 months, Ford had built 12,000 at its three-storey, 405ft-long, 56ft-wide, $76,000 facility.

Zastava, YugosLavia

The vast Zastava plant ‘built’ the infamous Yugo. Unfortunately it also produced guns, grenades and rocket launchers for the Yugoslav army during the Balkan civil war of the 1990s. As a result, the plant was put out of commission by a couple of well-directed NATO bombs.

Read more CAR magazine features