Mel Nichols penned Convoy, one of CAR’s most celebrated drive stories, which was published in February 1977. It was a never-to-be-forgotten journey in a convoy of Lamborghinis – a Countach, a Silhouette and a Urraco. Read the full, original feature below.

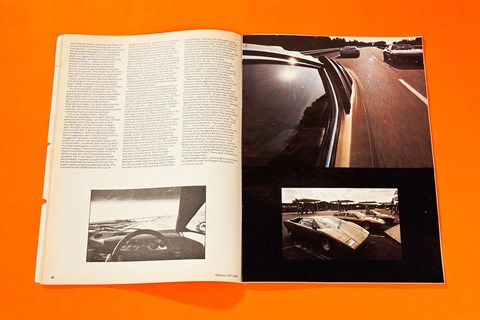

It had the unreal quality of a dream. That strange hyper-cleanliness, that dazzling intensity of colour, that haunting feeling of being suspended in time, and even in motion; sitting there with the speedo reading in excess of 160mph and two more gold Lamborghinis drifting along ahead.

CAR Issue 700: the biggest stories and best moments

Not even those gloriously surreal driving scenes from Lelouche’s A Man And A Woman were like this: that grey, almost white ribbon of motorway stretching on until it disappeared into the sharp, clear blue of a Sunday morning in France, mid-autumn, and those strange dramatic shapes eating it up.

What a sight from the few slower cars as that trio came and went! What a sight from the bridges and the service areas: they would have seen the speed! So would the police, of course, those same gendarmes who one after another apparently chose to look and drink it in, to savour it as an occasion rather than to act.

We hadn’t intended to travel so quickly when we left Modena with 1000 miles ahead of us. That we should, given the build-up, the delicious crispness of that early morning, the perfection of that road – and those cars – was inevitable; not to have done so would have been appalling now, for it was only a short time later that the French imposed their speed limits with a savage new will and such adventures may never be possible again. Yes, in German, in theory: but on those narrow German autobahns with their bumps…?

We arrived in Modena on Thursday night, spilling, tired, from an ailing Avis Fiat 131 hired with great difficulty at Milan airport: nothing has changed. For some inexplicable reason all the hotels in Modena were booked out, even our quiet little favourite the Castello out among the vineyards. Not even the talents of the desk clerk at the Real Fini could secure us a bed.

We lounged for an hour in his bar, glad to rest, while he telephoned. But Roger Phillips had a trump card: a key to the flat of Rene Leimer, the owner of Lamborghini, and we set off in the clapped Fiat again, weaving along backroads until we stopped at a trattoria in a village near Sant’Agata.

It was two in the morning but the place was still in full swing and Carlo the owner greeted Phillips like a long-lost brother and it was but moments until we had an excellent four-course dinner in front of us! No bill: there would be a grand reckoning when it was all over. And with that, we tumbled off to Monsieur Leimer’s beds, thankful that he was in Switzerland and thus spared the embarrassment of four guests.

Britain’s Lamborghini chief had come for his cars. About 10am he rang the factory. ‘Ah Phillips,’ – it was almost possible to hear sales manager Scarzi shrugging – ‘your cars? Perhaps this afternoon, perhaps tomorrow morning.’ The Urraco 3.0-litre was ready; even the Countach was ready. But the Silhouette…the Silhouette was still being painted.

Now Roger had been before, countless times, and David Joliffe who runs Portman garages, had been before and so had I; Steve Brazier, who runs Steven Victor, Lamborghini’s main London service agents, who hadn’t, could but tag along merrily for lunch and wonder. This time it was another of the remarkable Carlo’s establishments, a place of rather superior tone.

He waited on us personally, tirelessly and quite perfectly, recommending this, tut-tutting over that, sweeping away dishes not to his approval before we could try them and replacing them with others. We ate gloriously, and drank equally satisfactorily.

And then we were at the factory, that long fawn establishment set back a little from the road on the Modena side of Sant’Agata. Friday: no Dallara, no Leimer; not even Baraldini, that wiry little engineer who runs things now. He was off seeing the Germans about a certain forthcoming project that will consume a lot of Lamborghini’s time and production capacity and hopefully provide them with the economic answers they need, for things had taken a turn for the worse.

Leimer had been promised £1m by Italy’s answer to the National Enterprise Board. The little company needed it desperately but more than six months had elapsed and it still hadn’t been forthcoming, enabling them to begin putting their plan for future security into operation (see CAR July 1976).

Leimer, a Swiss, was and is, like other foreign investors in Italian industry, under pressure to get out. The Italian turmoil, the beginnings of a social upheaval, persists and foreigners are finding themselves accused of taking Italy’s money out for investment elsewhere. The fight goes on amid confusion and frustration.

There was no confusion, at that moment, down on the factory floor. The third strike of the day was over and the serious business of building Lamborghinis was under way once more. Ah yes – there was our Countach and there was the Urraco, waiting to go. Down on its own at the end of the line busy trimming Countaches – including an amazing blue one with gold-painted engine, gold cockpit and wheel arches, tricked up to look like Walter Wolf’s but apparently not in receipt of a 5.0-litre engine, and apparently bound for the highways of Haiti – was the Silhouette.

Around it clustered a team of men and women, buffing and polishing the fresh bronze-gold paint, painstakingly fitting the last bits and pieces. They’d be there for hours; there was no hope of our getting away before nightfall. The cars had to be checked and ‘sealed’ by the customs man from Modena yet, and waiting for him can be something else again. Better to wander around the factory, soaking it all up again. Thrilled just to be there.

We dined out yet again at the good Carlo’s and did ourselves no disservice at all. The grand reckoning was remarkably reasonable: about £25 for each of us for three excellent meals, a lot of wine and drinks and coffees. We availed ourselves of Mr Leimer’s hospitality yet again, but at an early hour this time. We were anxious to be on the road: next day, the serious business of ferrying three Lamborghinis to London would begin.

The noise of 28 cylinders, 12 cams, 14 sucking carburettors and eight howling exhausts rent the damp, still morning. Oh God, I’d thought, when Phillips tossed me the Countach keys; not the Countach to begin with. Not that, rhd drive and with no usable mirror on the left, to go through the villages and into Modena. Not that awesome beast with its awkward cabin and daunting visibility.

I tugged off my boots in order to have maximum control over the pedals deep down in the footwell, and while I was messing about the others were gone in a flurry of sound and exhaust vapour. I reached the gate, stopped to check the exit then eased on some revs and let the clutch out. The V12 spluttered and coughed; the clutch went in and throttle was pumped.

It picked up again with a roar as the car straddled the centre of the road, the clutch came out hard and we were away with a chirp from the fat Michelins and a quick waggle from the tail.

By the time I caught the others at the garage, filling up, I’d learned once more that my reasons for trepidation about the Countach were unfounded. How good it was, instead, to be back behind that outlandishly raked windscreen, with the little wheel between my knees. The first miles – yes, as little as that – had brought it all back: the incredible feeling of stability, the amazing precision of a car that has no other purpose in life other than to spear on down the road, as fast and as far as possible.

God, that feeling is so strong in the Countach it can take your breath away. And the pedals: I put my boots back on, those big insensitive boots, and never gave them another thought. We darted out into the traffic and stayed with it until we turned onto the motorway.

Even mild throttle and modest revs took us scampering past the rest of the traffic as we accelerated away from the toll booth to settle quickly into fifth for a steady 80mph cruising speed for the most, but varying it now and then to let the engines work at different revs for their first few road miles.

Running in with the Italian supercars – with any engine bedded in so thoroughly on the dynamometer – tends to be more driver discipline rather than the engine’s asking. They just feel ready to go, and indeed within two hours our speed was creeping steadily upwards until we were sitting on 110mph with the Fiats and the slower Alfas and Lancias moving out of the way well ahead as this £52,000 convoy sprang into their mirrors.

The pleasure to be had just from sitting there conducting the Countach at that steady, restful, seemingly slow speed was considerable. Again it’s the overwhelming stability that comes through strongest, and the absolute decisiveness of the car. The steering is not heavy, just solid. Turn it with the thumb and forefinger of one hand, s-l-o-w-l-y, and feel the car change direction without a millisecond’s hesitation. Feel it change direction at precisely the tempo and to precisely the degree you have commanded. Swing the wheel back and grin with pleasure as it comes back to its heading again. There has been no roll, nothing more nor less than you asked for.

Feel too, the messages being patted into the palms of your hands. I watched the Urraco and Silhouette, a little way ahead, riding over the bumps, with their tails dipping as one and rebounding so positively and economically. The Countach would go over the same bumps, and the feel alone said that it was dipping and rebounding even less than they were. And yet its ride is never uncomfortable. Oh yes, it’s firm, about as firm as that supplied by a modestly padded steel office chair resting on thick carpet when you jiggle up and down on it; but never uncomfortable. It simply feels to be honed as finely and magnificently as every other component in this king among supercars.

We stopped for petrol and food. The first of many crowds gathered around the cars and stared in silence. We swapped; I drew the Silhouette which Roger had pronounced ‘surprisingly and interestingly different’ from the Urraco even though they are essentially the same mechanically. He was right.

After the Countach, especially, but even compared with the standard Urraco I was startled by what appeared to be slack in the steering. It seemed very soft at the straightahead; turning it brought accurate response once the rim had moved a little way, but it just didn’t have the sharpness of the other 3.0-litre.

The explanation (see CAR Dec 1976) proved to rest with the Pirelli P7s with which the car was shod. They were allowing the rims to move in their walls before responding fully. The capability is there – even more so – it’s just that the Silhouette feels a lot softer. Its ride is similarly affected, and I lounged back in its tall tombstone seat and watched the Countach now snapping over the bumps in front of me, its tail barely bobbing.

The differences in the performance were brought home too: where Roger was accelerating relatively mildly in the V12, we had to prod the V8s quite decisively to keep up as he moved off from toll booths and past slower traffic. There was no disputing which one was boss.

We swapped again, in the bright sunshine of the afternoon now, and Roger removed the Silhouette’s roof. I switched to the Urraco with Steve at the wheel to try to take pictures. We were surging up the Aosta valley now, heading for the Mont Blanc tunnel and the air was clean and fresh and the sight of those two cars behind us, as I hung out the Urraco’s window with my camera, was magnificent.

A wide, straight road, mountains topped with snow rearing up on either side and the soft light of the dropping sun. I stayed out there until the cold wind of 90mph made it impossible to hang on longer: I asked Steve why he’d gone so fast. ‘Sorry, cock,’ he said in his best Cockney, ‘didn’t realise.’ I knew what he meant. We sped up to a more natural 120mph.

Not far from Aosta, we stopped for enough fuel to take us into France. I changed back to the Silhouette and buttoned up my coat. The lack of buffeting with the roof off was incredible. We were soon running at 140mph on the almost deserted autostrada, and even at that speed there was little by way of noise or wind intrusion. Amazing.

Mont Blanc loomed ahead; the sun was low and dropping fast, and the air was getting cold. The heater, full-on, warmed my legs and chest while my face froze. But what an evening – flowing so quickly and effortlessly up that mountain and finding that the Silhouette and its Pirellis had more grip that I might have imagined. Alone again in a real sports car; a sports car, what’s more, with the power to eat those bends and catapult past the trucks. For I know not how long I endured perfect pleasure.

I didn’t realise how cold I was until we stopped at the customs control at the entrance to the Mont Blanc tunnel; like a fool I volunteered to be a passenger again for the descent, although I suspect I gained just as much reward from watching the Countach and Silhouette darting through the endless downhill bends ahead of Steve and me as I might have from driving myself. There was barely a car on the long, quick autoroute up to the Swiss border and we covered it at a steady 140mph cruise, the cars hardly seeming to work.

Night was coming quickly and we wanted to be within reasonable striking distance of the Dijon-Paris autoroute before stopping. After we’d halted for coffee at a bar whose owner claimed that his front door was in France and his back door was in Switzerland, the Silhouette was mine again: Roger took a break while we covered the bumpy backroads taking us across the Rhone and on towards Nantua with the sort of ease that can be had only in a true grand touring car; it’s at times like these, with a few hundred miles under your belt, and the going is growing more difficult and tiring that you appreciate them most.

They are so very much in control, so much within themselves. Their reserves are your reserves: we came over a crest and there, on the wrong side of the road with no hope of making it, was a rolling, juddering, wound-up 2CV trying to overtake a truck. There was a small pull-off area; the Silhouette darted into it as the Deux Cheveaux sailed past. David and Steve saw the dust and followed suit. The rock wall lining the road resumed again, and no doubt, so did the 2CV driver.

We stopped at the first likely hotel, and that’s how we discovered France’s answer to Fawlty Towers; a tarted-up place called the Chateau du Pradon terrorised by two mad cats called Antoinette and Voltaire, with its wallpaper tacked on with sticky tape and decidedly curious plumbing but comfortable beds, humorous staff and an impeccable restaurant.

The Urraco went into the garage and so did the Countach, at a pinch. But the Silhouette’s spoiler was just too low to clear the ramp. It stayed outside, and at six the next morning, with the others already throbbing out of the courtyard, I found that the windscreen was covered in ice. They didn’t hear me shout, and while I was still scraping the screen clear, they were through nearby Nantua and gone.

The car had come to life as easily as ever despite the cold and after warming it up carefully it was ready for an attempt to catch up. But was there ice on the road? The first few bends suggested not, just as they also began suggesting how much roadholding was available in this new little Lamborghini. And what a road on which to exploit it! Running along the side of a lake and then climbing up through first one range of hills, dropping, then rising and descending through two more over a distance of about 50 miles, and barely a straight anywhere.

Without the car being taxed in any way, it simple devoured that road. Keeping the V8 in mid-range and just occasionally giving it its head for a moment coming out the bends brought more than enough speed; despite those curves, the speed was rarely below 70mph and frequently around 100. The bumps mid-bend, and they were often frightful, could not throw the Silhouette off-line. Wet patches encountered under brakes into hairpins did not make it budge an inch.

Ah, how well it could all be felt through that leatherbound wheel and the pliant but ideally-controlled suspension. To experience it is to understand just how good a car can be; how swiftly but safely you travel, with never a wheel out of place or a trace of drama. Just pleasure.

The others were waiting, dawdling along, on a straight preceding a vital junction. The road from there took us over yet another set of hills, and as we reached their peak we looked down upon a sea of mist filling the river valley below. It was eerily beautiful.

Phillips knew I would want to stop for pictures and before I could overtake him to call a halt he increased speed, and until we ran into the mist ourselves those three cars tore down through the bends, one after the other, each of us listening to the engines of the others’ cars as the gearchanges came thick and fast; each of us watching the progress of the other cars through the bends, and not for any contest but simply for the delight of seeing how flatly and tidily the three gold beasts obeyed their drivers’ commands.

We reached Bourg-en-Bresse as the mist began to ease a little. On the pavement in one part of the town huddled a group of men. One of them saw us coming. He stopped out into the road and pumped his arm furiously to summon his companions. They lined the road and watched in awe as we wailed past, whatever they were doing forgotten. Leaving the town, we came upon a Citroen GSX2.

He was sitting on a steady 100mph, and brought me, at least, back to reality. It was easier for us to hold that speed, and we had a great deal more in hand. But here was this little 1200cc saloon, kids and all, scooting along at the maximum speed vision would permit. He could drive too, and we were content to sit behind him until we had really clear road.

The Countach reached the motorway west of Macon first. And after such a stirring early morning warm-up who would have been able to resist giving such a car its head? Roger took it hard up through the gears. I dropped my window to listen, and could still hear it above the sound of the Silhouette’s V8. Steve and I did our best to catch up, running on to 165mph only to see the Countach still disappearing into the distance – and the unobstructed vision of a gendarme.

He watched us come, one by one, turning his head after each of us. We pulled into the Restop a kilometre of so up ahead; so did he. But he just parked his bike and wandered over to look at the cars with a nodded hello. A whole busload of gendarmes came over to join him, and so did another two cyclists. We watched from the windows as we ate a breakfast. And then the police watched us go, accelerating away at a pace merely brisk-ish for us but very fast to an onlooker. None of the gendarmes moved.

Somehow, we knew we were going to be all right, and for the rest of the day our speed stayed around 120mph, with some spells at both 140mph and then a little over 160mph. So we flowed along that silver-grey ribbon of road, disappearing north into a blue, blue morning. It was a big, wide-open feeling; lulling and warm.

You felt relaxed, hand just resting on the wheel, the car re-affirming its grip on the road and its arrow-like direction every single instant. It made you feel sharp, provided you with an alertness that can last hundreds of miles at a time. Even nearing their top speed, these cars feel so free from stress, and so do you.

We ran on and on and on, and it really was like something from a film, with first the Countach flowing out to pass a slower car and then peeling in again, and then the Silhouette, and then the Urraco. We stopped for fuel and one quick break on the way to Paris, and then again on the way to Lille, and it was after that that the trip reached its climax.

I was with Roger in the Countach. We were running at around 120mph. In the mirror Roger saw a Jaguar XJS closing fast. He changed down to fourth and opened the Countach right up. It surged ahead with staggering force, and precisely as the Jaguar came alongside we had matched its speed at 155mph. We were in top again now, the throttle still open, and we left the XJS as if it were standing still. At 185mph we were forced to lift off, and as we slowed I saw that both the Silhouette and Urraco had come past the Jaguar too.

The pain was more apparently than its driver could bear. He caught us up, took a long look and then pulled off to the inside lane and proceeded at 80mph; and if this sounds irresponsible I would, in principle, be forced to agree. But I was there, and the road was empty and we did not block his path. We had too much in hand for that, and I can only tell you again that even at that speed a Countach is stuck down solid as a rock, never twitching from its path while behind your head is this incredible, ferocious noise: the V12 in full cry.

It was something of an anti-climax after that, although the pleasure of course went on. For me it did, anyhow, for I took the Countach over again and was able to enjoy the potency of that engine as we worked down the coast to Calais, hanging back as the lead car with its sight-seeing passenger set the pattern for overtaking, and then blasting through in second or third and being both thrilled and amazed by the acceleration and the ease with which it can be used and is controlled.

By five o’clock we were on the ferry, and it was all coming to an end. There were just the customs clearances on the other side and then the run back to London on the beleaguered roads of a misty Sunday night.

We were not tired when we stopped, at last, just as I had not been tired a few months before when I’d driven an Espada 900 miles in 13 hours over much the same route. One just switches these cars off and gets out. And begins to relive it all.

I’m still reliving this particular trip. I always will be.

Read more of our greatest adventures drives on CAR