The Japanese are about to attack the most difficult market of the lot: supercars. Domination of the small and medium-sized saloon markets, worldwide, has been accomplished. They can also check off the small coupe sector. And the big saloon market, never a Japanese forte, is about to get a worthy couple of Asian challengers, in the form of Nissan’s Infiniti and Toyota’s Lexus.

But supercars are different. Japan is the world’s most successful car producing nation because Japan builds the world’s most sensible cars: good value, reliable, well researched, well equipped, tidily finished. Those values count for naught in the emotionally supercharged world of supercars. Common sense means nothing. Ditto practicality. The big master computer that helps the Japanese tap into the thought patterns of Western car buyers will blow a fuse trying to work out why people buy Ferraris and Porsches and Lamborghinis. There are no sensible reasons. No logic. Instead, what’s needed is soul, inspiration and emotion. Over the years, these are the very things the Japanese have shown themselves wanting.

Until now. Honda, long regarded as the most inspirational of its country’s car makers, and now imbued with a strong image after its trouncing of Ferrari, Porsche et al in formula one racing, is only a year away from launching a supercar that exposes Porsche as a builder of mainly obsolete cars (after all, the company’s last all new design was introduced more than 10 years ago), and highlights Ferraris as being cramped, noisy and uncomfortable. The new NS-X will be built in much greater numbers than any other powerful mid-engined car, and has an on-paper specification superior to most Ferraris or Porsches (all-aluminium monocoque, aluminium body, full-wishbone suspension twin-cam four-valve heads using variable valve timing to give 90bhp per litre, perfect weight distribution, and more).

To boot, the car is great fun to drive, and easy to drive, too. No mid-engined high-performance car has ever combined those virtues before. All-round visibility is panoramic, the seats are comfortable, and the cabin is tasteful. Its cockpit says 1990. Step into a Porsche 911 and you step back 20 years. Step into a Ferrari GTB and you’re likely to bang your thigh on the sill, and your head on the roof – never mind having to cope with the off-set pedals, the poor rear visibility, and the sheer weight of the controls. By comparison, the Honda pampers. But it also entertains.

Honda has never understood why supercars have to be silly cars. It wanted to make a mid-engined two seater that the effete, as well as the fit, could enjoy; in which Sennas could get exhilaration and everyday shoppers satisfaction; a car that would be reliable and well made and quite simple, but that would also do 170mph (or thereabouts), make all the right noises and satisfy the sensibilities.

And Honda has succeeded. Quite spectacularly, in fact. During a full day spent driving two different NS-Xs (one manual, one auto) at Honda’s Tochigi test centre, about 60 miles north of Tokyo, the cars barrelled around the high-speed bowl at 150mph, tracking straighter than either the 911 or the GTB (both ’89-spec cars) that Honda conveniently had on hand, and generated less wind noise, too. But – surprise surprise – they generated more of the right sort of noise: a superb deep-voiced bellow under acceleration that infiltrates the cockpit, and gushes from the rear exhaust pipes. Neither the 911 or the GTB sound as good, and that amazed me.

Later that day, on the handling circuit which snakes around inside the high-speed bowl, offering a good variety of tight low-gear bends, and quick, can-I-take-this-flat-or-not? corners, the NS-X showed the flip side of its abilities. More forgiving, more predictable than the Porsche, and almost as fast on the winding bits. Lighter, far less tiresome, and almost as quick as the GTB. Better interior, just as wide a torque band, much better gearchange, just as good at braking, although it lacks the turn-in sharpness of the Ferrari, and, ultimately, its animal alacrity. I told the posse of Honda engineers on hand (including engineering chief Nobuhiko Kawamoto) as much. ‘We know. We are working on those problems. Don’t forget the car is still a year away from production.’

It will be built in a new factory at Tochigi, where production is expected to be 6000 cars a year – vast by the standards of170mph, mid-engined machines. The US will be the biggest market, although Europe also promises to be lucrative. The target price is ‘about $60,000’. Expect the NS-X to cost about £40,000 in the UK, which is 944 Turbo money. The on-paper comparison does not read kindly for the Porsche: a 13-year-old, front-engined four-cylinder design using conventional strut suspension and fitted with a steel body, versus a mid-engined, aluminium supercar using a brand new V6 motor that is the most efficient supercar powerplant yet built, and riding on forged aluminium wishbones. Porsche, which has been very lazy for a very long time when it has come to giving us new metal, is about to get a rude shock. And not a moment too soon.

The cars I drove in Japan used 3.0-litre singe-cam-per-bank, four-valve-per-cylinder engines, developing 250bhp. The production engines will be stronger. New heads, using twin cams per bank, are on the way. Good for 270bhp, they feature Honda’s radical variable valve timing, first seen on the new Integra, recently launched in Japan. Variable valve timing is an ingenious way of increasing an engine’s effective torque band, and of increasing top-end power. At low and medium revs, low lift cam lobes, giving minimal overlap, are used to operate the valves – ensuring good pick-up and tractability. As the revs increase – at a point where conventional engines start to run out of breath – extra cam lobes (one for every pair of valves) and rocker arms are activated, increasing the lift and overlap of the valves, and thus greatly increasing top-end power. The Honda’s system is the first to alter the valve timing and the lift, and is thus much more advanced than the existing systems such as the one used on the Alfa Twin Spark engine. Maximum power will be developed at 7300rpm, and the engine will be capable of running to 7700rpm.

The 90deg V6 engine is sited transversely and drives the rear wheels through a five-speed gearbox or a four-speed automatic transmission. Four-wheel drive was considered, but rejected: it added more than 200lb, and low weight is regarded as crucial. Four-wheel steering was also considered, but rejected for the same reason: with it, the mass would have increased by just over 100lb.

The search for light weight demanded the use of an aluminium monocoque and body panels. No steel is used in the body, nor glassfibre. Using aluminium rather than steel saved 440lb, reckons Kawamoto. The car’s no featherweight, all the same. Yet its 2816lb compares favourably with the (shorter and narrower) 944 Turbo’s 2970lb, the Ferrari GTB’s 2805lb, and the 911 Carrera’s 3190lb. Using the new quad-cam variable valve timing unit, the NS-X will enjoy comfortably the best power-to-weight ratio in its league.

As with most sporty Japanese cars, the detailing of the NS-X is excellent. The engine – unrelated to the Legend’s V6 – not only sounds superb, it looks terrific. The forged aluminium wishbones which hang off each corner are beautifully crafted; there is a formula one type simplicity about them. Coil springs soften the bumps. Fifteen-inch diameter wheels are used in the front, 16in rims at the rear. They, in turn, wear 205/50 and 225/50 rubber. Yokohamas were fitted to both test cars. The fronts carry 43 percent of the vehicle’s weight; the rears 57 percent. Anti-lock brakes stop the big ventilated discs from locking, and speed-proportional power steering will be offered – but probably only on the automatic version.

Although the car is designed as a strict two-seater, roominess is important. Headroom, legroom and shoulder room are of saloon car, not exoticar, proportions. Similarly, the boot is larger than the letterbox-sized supercar norm. It’s shallow, but tolerably wide and long, and is helped by the NS-X’s long tapered tail – which also helps reduce yaw. The forward bot is virtually useless as a luggage, or oddments, repository. There is no rear shelf: the rear bulkhead is only inches behind the driver’s shoulders.

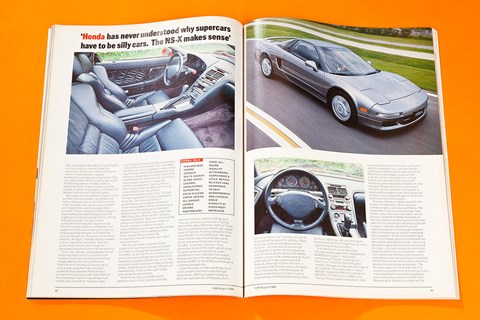

Without doubt, the car is handsome, and it will turn more heads than a 944 turbo. But in Honda’s effort to make the NS-X look like a supercar, it has been a touch too slavish in following Europe. The NS-X looks like a Ferrari – not surprising given that Pininfarina had a hand in the design – a fact to which Honda officially gives a wide berth – but not a particularly distinguished one. Given that Honda has pumped out some very attractive, original cars in the past few years (notably the CRX and the Prelude), you may have expected better. But the NS-X looks neat and clean and elegant, and the Yanks will love it. Despite the importance of America, however, no Targa-top version will be offered.

The doors open wide, allowing easier access than does a Ferrari, and, once behind the wheel, folk used to everyday saloons and coupes won’t feel in a foreign land. You don’t struggle to see over the dashboard, as you do in a Countach; you aren’t cut off from the outside world behind, as you are I an Esprit; you don’t sit skewy in front of stupid instruments and switches, as you do in a 911; and you don’t have to put up with a silly driving position and no headroom, as you do in a GTB (and most other Ferraris, for that matter). The combination of low seating position, and mid-engine does not affect the driver’s visibility or comfort, and that’s just the way it should be. The architecture of the dashboard is clean and attractive – in the Honda tradition. A large binnacle, right in front of the driver, contains all the instruments, Ferrari GTB-style. The gauges themselves are all large, clear white-on-black affairs.

During the pre-drive press briefing, Kawamoto and the other senior Honda engineers on hand (and every senior Honda engineer was on hand), spoke about being influenced by aeroplanes, when the design was done. At the time, I thought it was the same fatuous aircraft association that Saab and Rover try to milk every time they make excuses for being behind the Germans. I underestimated Kawamoto. The interior of the NS-X plainly does have an aircraft feel. The driver and passenger sit in quite separate, heavily enveloped compartments, rather like fighter pilots do. The two seats are separated by a high and wide centre console, on top of which is mounted the stumpy, wedge-shaped gearlever. Both the driver and passenger can wedge themselves comfortably into their areas, knees butted against the door and centre console, better to resist side forces and, in the driver’s case, better to control the car at speed.

A large left footrest is also conveniently sited, for the driver. A reach-and-rake-adjustable steering wheel – a beautifully compact, three-spoke design – is at chest height, and doesn’t badly obscure the large gauges nestling behind it. Some of the switchgear – ugly, hard plastic switches – are on pods either side of the steering wheel, and mover with the wheel during its adjustment. The seats are heavily bolstered, and offer excellent lateral and thigh support. When your belt is clipped up, your torso is snug among the cushions.

Ready to go. The engine engages smoothly, and quite silently. Give the throttle a jab, though, and the silken beast resting behind your shoulders will snarl. It’s a deep, aggressive, inspired bellow. The exhaust note will tingle your spine, even if the vibrations do not (for this is an exemplarily well balanced unit, as you would expect from Honda). The message is clear enough: there’s Sumo-wrestler-sized muscle on offer, rather than the pert, judoist-sized strength usually offered by sporty Japanese machines. But the brawn is matched to elegance: that much is clear, on the track.

The clutch is quite light for a performance machine, particularly by supercar standards. First gear is engaged a little notchily: the clutch takes up smoothly, the engine digs deep into its rev band, and the NS-X growls its way out onto the high-speed bowl. The view out the front is panoramic, a deep, acutely curved windscreen, bordered at the bottom by the sweep of the front wings (the nose itself is well out of view). Check the rear-view mirror, and you also get a generous view of the track, as well as of the rear wing, sitting truculently on the sweeping tail. Rear three-quarter vision, one of the traditional bêtes noirs of supercars, is generous.

Around and around the bowl, the car touching 150mph on the straights, the engine braking pulling that back to about 120 on the banked corners. The bends are actually quite tight – you can hear the front Yokohamas giving mild protest – but the overriding impressions are of the stability, the lovely accelerative below, and the absence of wind noise (I had no companion with me but, had I, we could have conversed comfortably at 150). Swap from manual to automatic. A fine marketing idea, fitting an automatic into a supercar (sacrilege and desecration! cry the enthusiasts), but the auto in the NS-X hunts far too much between changes: it’s too indecisive.

The bulk of the day was spent on Honda’s handling circuit: a track on which Senna and Prost and their McLarens have been known to while away time. Of course, we’re on Honda’s home territory – if the car doesn’t go well here, what hope has it got? – but the circuit is difficult enough to truly test any car. We – self and four other European journalists (from Auto Motor Und Sport in Germany, Sport Auto in France, Quattroruote in Italy and Automobile Revue in Switzerland) barrelled around the track for the best part of four hours, wearing the Yokohamas to mush.

Whereas the NS-X is more impressive than the 911 and GTB on the bowl, it isn’t on the tight stuff. It understeers a touch too much, and when the understeer gets bad the front Yokohamas start shaking and streaking like a demented ninja. Keep pushing, and you and the Honda will commit hara-kiri, for the run-off areas at Tochigo are small. Honda is trying different front rubber, with greater sidewall rigidity; that may stiffen the front, improving the wayward wail of the tyres. The NS-X rolls a little more than the GTB and the 911, a corollary of its softer suspension. Given that Honda is trying to court fat-bellied Americans, as well as fiery-blooded Italians, the extra chassis suppleness is sensible. And the roll doesn’t affect the tidiness of the Honda much. More worrying, though, is the car’s tendency to do a deceptive oversteer flick when really tanking on: I suspect a lack of chassis rigidity. And a Honda engineer later confirmed that the next prototype the company builds will have extra solidity.

The gripes are more peccadillos than major criticisms, though. For a car still a year away from production, the NS-X is uncommonly and (for Ferrari and Porsche) worryingly good. There is a gracefulness that the sharp but tail-happy 911 and the heavy-to-drive but lively GTB just cannot match. The Porsche and the Ferrari entertain more, and the Ferrari is more obedient to both steering inputs and throttle changes. But both cars require more work, for only marginally more reward. The Honda is a rewarding and easy car to drive at nine-tenths. At the outer limits, it may not be quite as fast or as entertaining on a winding road, but this fact will cause Honda no grief. Just as important, the single-cam-per-bank engines we drove are at least a match for the 911’s and GTB’s engines: chances are the quad-cam engine will be better. Its gearchange – although still a little notchy – certainly betters the Ferrari and Porsche shifts. Its brakes are a match for Europe’s finest and, unlike the 911’s they won’t lock when what you want is roll.

In short, Honda has breached the gap between invigorating supercar and friendly sports car. It probably won’t cause Ferrari any worry, for no amount of Senna-Prost one-twos will give a company that also makes Civics enough cachet to outdo Enzo’s mob. And it won’t hurt the dear old 911, which soldiers on and on. But it’s going to hurt the 944 range, on which Porsche depends for its volume.

More important, it’s going to put powerful, exhilarating, attractive mid-engined muscle cars into homes that have had to make do with less. It will bring a whole category of car into the reach of those who cannot afford Ferraris and Lamborghinis, or haven’t got the patience to put up with their waiting lists or their mechanical foibles. People who settle for the Honda will not be disappointed, not if my opening shot at the car was anything to go by. For the NS-X is not only a wholly competent car, which was to be expected, given Honda’s determination to get it right. To boot, it is a characterful, entertaining machine: one that has soul. The Japanese, it seems, have opened the door to Europe’s last remaining automotive secret.

Read more CAR iconic car features here