► The new 2019 TVR Griffith

► CAR magazine’s detailed preview

► Will Welsh factory hold up project?

The rebirth of the TVR nameplate is being delayed by questions over how the new Welsh factory needed to build the Griffith is funded. It’s emerged that European Union (EU) rules are forcing a longer tender process than anticipated, pushing back the likely delivery date.

When the TVR Griffith was launched at the 2017 Goodwood Revival, bosses talked of a launch in early 2019, but local government support for the factory in Ebbw Vale, South Wales has complicated matters. The Welsh government bought a 3% stake in TVR and issued a £2 million loan to incentivise the factory upgrade – but to meet EU rules, the tender process must now take place over seven months across Europe, rather than just local companies.

This means the tender won’t close until January 2019 and boss Les Edgar has confirmed that the factory will take around half a year to refit after that date – suggesting that no new cars are likely to be in production before late 2019. However, Edgar added that the very first cars could be built elsewhere.

Read on for CAR magazine’s detailed preview of the new TVR.

Up close and personal with the new 2019 TVR Griffith

The car sits up on stands without its wheels, glazing, bonnet or headlights but still its shape takes my breath away. The lean detailing, conspicuous aerodynamic proficiency and thudding V8 are pure Le Mans racer, while its just-so proportions, wieldy size and self-evident lack of mass adhere to the timeless blueprint of the great British sports car. It’s a potent blend. Quite apart from how it promises to drive, to these eyes the new TVR Griffith looks sensational.

It might lack the extravagance of the Sagaris, the swansong creation of TVR’s last era, but just as you try to classify it is as cute you’re floored by an evil-looking, full-width diffuser and a yawning pair of side-exit exhausts. ‘Cute’ is suddenly entirely inappropriate. TVR is not cute. And now the Griffith’s here as rolling, bellowing proof that TVR is not dead either.

We’re at Gordon Murray Design in Surrey, late August 2017. In 10 days’ time the new Griffith, the first car of TVR’s new dawn, will be shown to the world at the Goodwood Revival. Before then this striking work in progress must be caressed into a finished, fully functional prototype. All around it, like a very neat airliner crash in reverse, scattered parts sit on bubble wrap awaiting their moment. With the devoted industry of many, many pairs of gloved hands, ideas and calculations and deals and CAD models will, over the course of a hundred hours or so, become a car. And the car should, if those calculations are on point, lead a renaissance.

TVR’s new owners, a consortium of petrolhead investors, acquired the company in 2013. CAR first met chairman Les Edgar in 2015, when we drove his rapid (and rapidly appreciating) Sagaris. ‘I managed to get the previous owner [Nikolai Smolensky] on the phone and convince him that the name deserved to be repatriated and brought back to life. That struck a chord with him; the transaction was bizarrely straightforward after that,’ explains Edgar.

‘He thought that the car TVR needed to build next couldn’t be done for less than £150,000, but that TVR couldn’t charge that kind of money.’ Edgar agreed that £150k was too much for TVR’s comeback car, but felt he could do it for less. The Griffith, Edgar asserts, is the £90k ‘affordable British supercar’ with £135k performance.

Click here to browse secondhand TVRs on our sister site Classiccarsforsale

Edgar’s innate understanding of the TVR brand and exactly what its resuscitation required is evident in the doors he chose to knock on next. Life’s about timing, and TVR needed an affordable high-performance chassis concept just as Gordon Murray needed to demonstrate there was more to his iStream concept than little city cars. The fit was heaven-sent. iStream takes TVR’s traditional tubular steel architecture and reinvents it for a new era and a new level of performance, the combination of steel structure and bonded composite reinforcing panels creating a level of stiffness ‘comparable to a carbonfibre tub and far in excess of that of a bonded aluminium structure’ according to Gordon Murray Design’s (GMD) technical director and former F1 man Frank Coppuck.

That Murray was also the perfect man to develop the high-downforce, super-stable aero concept that’d allow Edgar to safely pursue TVR’s traditional dislike of nannying electronics was the icing on the cake. And the cherry? That Edgar plans to see TVR back to Le Mans. And when you’re planning to do that with a production sports car, Murray’s credentials – his McLaren F1 won Le Mans outright in 1995 – are impeccable. In return for the chance to prove iStream in a production sports car, GMD offered TVR expertise and credibility.

TVR grandee: Peter Wheeler obituary

Next up, an engine. Edgar considered a straight-six but he’s a devoted worshipper of big V8s and their torque. Ford and TVR have history. Cosworth and Ford have history. And so Edgar’s efforts yielded a Cosworth-fettled version of the 5.0-litre Ford Coyote V8 you’ll find in the Mustang and F-150. At a stroke the Cosworth engine brought bags of performance, further credibility, a cute link to another affordable giant-slayer of a car, the Sierra Cosworth, and implicit reliability, not to mention the promise of availability no matter how many cars TVR cares to build. Cosworth, TVR, Gordon Murray – suddenly the dream began to look worryingly like a workable business case. And so, almost exactly three years ago, the Griffith began to take form, first as a seating buck.

‘I didn’t think a buck would tell us anything a perfect CAD model couldn’t, but we changed so many things: better visibility, better access, and the space for two men to sit comfortably side by side,’ says Edgar, whose background is in electronics and displays ‘for the MoD mostly, submarines and jet fighters’ and computer games. The Griffith’s sills are indeed strikingly slim, and the ‘floating’ centre console uses a compact, McLaren 720S-style portrait screen orientation.

The seats are very Gordon Murray – to save weight the adjustment is manual, without a single motor – and very TVR, with a four-point harnesses (seatbelts are an option). ‘For us it all comes back to the driving experience,’ smiles Edgar. ‘Strapping yourself in feels right for a TVR.’

Less Gordon Murray is a 5.0-litre V8 in the nose… ‘Yep, that’s more of a Les and team thing,’ smiles Edgar. ‘We also had some debates over the size of the car, and particularly its width. Gordon loves small, light cars but sports cars have grown over the years. A Sagaris now looks diminutive next to a Ford Focus and I didn’t want that. We needed presence.’

‘We had to present a carefully constructed case for making it wider,’ laughs GMD’s Coppuck. ‘Go in cold and Gordon will have you for breakfast. But when you’re thinking about racing you need width, not least because the wider your car, the wider the rear wing you can run on it.’

‘We’re around 60mm taller, 100mm longer and 70mm wider than the Wheeler-era cars but still 150mm shorter than a 911,’ explains Edgar. ‘Racing is important to us, and you get better handling with a wider track, on road and track.’

Designing an all-new TVR, while an exciting opportunity, proved challenging, not least because the marque’s back catalogue lacks any design continuity. One fairly retro proposal was developed to an advanced stage before being binned. Edgar cites the timeless good looks of the 1991 Griffith and the later T350 as inspirational machines. Elements of the design were further honed as the new Griffith was scaled up from one-third to full size, and it was a 1:1 scale model that was shown to 400 deposit holders in March 2017 (500 Launch Edition Griffiths will be built).

‘We ran the viewings in shifts, and in three-quarters of them the response was a standing ovation – a massive moment for us,’ says Edgar. ‘Six people pulled out. Of those, five were Sagaris owners expecting something wilder.’

As Edgar and I talk our way around the car there’s no let-up in the frenzied workshop activity. The man artfully blends the roles of salesman, creator and kid on Christmas morning. His enthusiasm is infectious, his clarity of thinking striking. Every aspect of this car, from the engine to the driving position to the look of the HMI’s homescreen has required decisions. Edgar’s had the confidence, vision and sensitivity to make a call on each and every one of them.

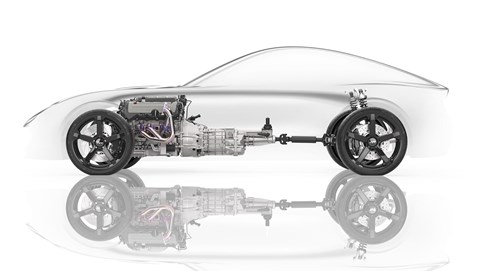

‘The engine is absolutely as low and as far back as we could get it,’ he tells me. ‘Cosworth add a lightened flywheel, new management and dry-sump lubrication. The sump means no oil starvation on track and a more compact engine, so we can get it even lower and further back – it’s truly front-mid-engined. I was a little worried that, with the introduction of the Mustang in Europe, Ford would be reluctant to help. I was wrong; they’ve been hugely enthusiastic.

‘We haven’t set the power figure but I’ve always said a 1200-1250kg kerb weight and a power-to-weight ratio of 400bhp per tonne. We’re on course for that [indicating a 480-500bhp output – the engine makes 415bhp in the Mustang]. We have the powertrain installed in a Cerbera mule, and at Dunsfold it blew past a standard Cerbera like it was standing still.’

Edgar pulls out his phone and shows me a video; an onboard of a standing start in the powertrain development car, TVR operations director John Chasey at the wheel. Chasey nails the throttle, each shift of the six-speed manual ’box heralding another storm of V8 noise. The two men grin like schoolboys. ‘That car has no sound deadening of course, to get the weight of the Cerbera down to that of the new Griffith. The finished car won’t be quite that loud…’ laughs Edgar.

‘We haven’t released a 0-62mph time but top speed will be of the order of 200mph, and the figure I’m interested in is 0-100-0mph. With our kerb weight that should be really strong. The thing would stop sharply with Fiesta brakes, let alone the Griffith’s AP set-up.’

Two things strike you as you circle the new Griffith, much of its mechanics still visible as the car awaits outstanding bodywork elements. The first is the beauty of the car’s iStream construction and its top-drawer componentry. Brakes are AP; huge ventilated discs with six-piston front calipers. Between double wishbones all-round sit gorgeous Nitron spring and damper units. The other is its exhausts. You can’t miss them, swathed as they are in NASA-spec heat shielding like priceless satellites ready for launch.

Cooling, clearly, will be a challenge. ‘Heat management is one of the biggest issues when you’re engineering a car like this,’ explains Edgar. ‘You think, the catalytic converters are at 1000°C, and you might come storming down the motorway and straight into a traffic jam. The car has to be able to cope.’

To that end the Griffith employs a very neat, very Murray solution. You’ll notice the large vents in the upper surface of the bonnet. At speed, high-pressure airstream is drawn down through these to the exhausts and,4 encouraged by the low pressure under the car, down out of the body. At low speeds and at a standstill the exhausts simply vent directly upward through the same apertures, assisted by the inarguable truth that hot air rises. ‘We didn’t want any additional complexity – wherever possible we’ve gone for God-made rather than man-made solutions,’ says Edgar.

Like Murray’s McLaren F1 and SLR McLaren-Mercedes before it, the Griffith doesn’t use a rear anti-roll bar. ‘Increased traction is the main benefit,’ says Coppuck, adding that with the right suspension set-up you don’t need the bar. You can see why Edgar’s confident of some pretty stellar acceleration times, even though the car lacks launch control. ‘Launch control? That’s called your right foot,’ says Edgar. ‘We have ABS and a multi-stage traction control – it’s not a car only for the bold and the brave – though naturally you can turn it off.’

The Griffith wears its iStream skeleton with pride, and as you think it all through the advantages keep coming. The sills are wafer-thin compared to those of a Lotus or a McLaren.

According to Coppuck the Griffith platform is easily modified to create a 2+2. The non-structural roof spars can be removed without fuss for the convertible, likely the next derivative. (A track-ready version should follow.) iStream also eliminates the difficult (and expensive) task of locating hard points in a composite structure. Rigidity, though, is comparable.

‘With this chassis we’ll easily pass federal crash regs if we go down that route; 50mph and rear impact,’ adds Coppuck. ‘There’s room for development too. A switch to aluminium for the structure will reduce weight by a further 30 per cent.’

With no expensive tooling or assembly equipment required, iStream makes the task of setting up TVR’s factory a much more palatable financial proposition than would be the case with conventional automotive manufacturing. If Edgar, Murray and Coppuck have anything to do with it, the build quality will be up to scratch too.

‘Another benefit of iStream is that we can achieve OEM panel alignment,’ says Coppuck. ‘This is because we bond the integration panels [the layer between the core structure and the outer panels] in place, with the adhesive giving us the scope for adjustment. The fit and flush we had on the first SLRs was poor by comparison.’

That the new Griffith was shown to the world in what was also TVR’s 70th year is further evidence of this venture’s pleasing rightness and sense of symmetry. As I leave, GMD and TVR staff still swarm all over the car, fitting glazing, offering up control panels (as minimalist and idiosyncratic as you’d expect, with machined brass and aluminium touchpoints over tried and tested switchgear) and moving with the choreographed ease of a team long since bonded (GMD considers TVR less a client, more a part of the team). Fuzzy sweatband-like belt-buckle protectors strive to stop inadvertent marks to the paint, whose incredible finish has asked for no fewer than six top coats.

A couple of days later and just 24 hours ahead of shipping, the car is finished. It sits in the now quiet GMD workshops looking as much a statement of intent as a sports car. Its taut form, malevolent presence and refreshing lack of show-car superficiality – this is a working prototype, and will go into heat testing straight after the Revival – add a further sheen of credibility to a project that already shimmers with the stuff.

Edgar, eyes bright, irrepressible smile on his lips, is happy like a lottery winner. ‘When we bought TVR we weren’t prepared for the groundswell of positivity and support. Everybody has a TVR story, and that support sweeps you off your feet, pushes you on. Would we have done it had we known the mountain we’d have to climb? Are you kidding? The chance to bring back a 70-year-old sports car name and, from a clean sheet of paper, build a brand new, balls-out road racer and take it to Le Mans? It doesn’t get any better than that.’

What do you think of the new TVR Griffith? Be sure to sound off in the comments below